Although the mythology of the material and intellectual cultures we know as 'Greco-Roman' is Europe's oldest inscribed tradition, that of Ireland and the 'insular Celts' must come next, albeit the written form of it is from a much later date. In particular, it often excels and exceeds the Greek material by its apparent strangeness and stylised 'otherness', yet as a source of pagan myth it needs – like the Norse sagas and Edda texts – to be treated very carefully as it is told by christians, unlike the Greek and Roman material which comes from pagans.

Nonetheless, the Christians did not have much in the way of myth to call their own, except for the 'Old Testament' materials and the early saints' lives, many of which were based on pagan tales, in their style and often in their narrative content: These were essential to pad out its own religious narratives and replace (or at least displace) the contents of the potent oral-transmission culture with a literature-based alternative.

It is worth noting a number of things about southern-European pagan religious culture, however, before framing a debate of paganism vs christianity in terms of oral transmission culture vs. literary culture: Firstly, it is worth remembering that – since the advent of the Hellenistic era in the 5thC BCE – that literary culture became an important stalwart of Greco-Roman societies, and seems to have become a primary mode by which people came to understand their religion. There were certainly traditional aspects to the culture to a late period, but by the advent of christianity, this was being displaced. The role of the priesthood and attendants in many of the most important temples was generally fulfilled as a fixed term civil office by the worthies of Greek and Roman society, so – unlike the traditional and esoteric forms of learning that Gaul (and Britain's) professional priesthood had to undergo, these offices were losing their mystery. Mystery remained the province of cult-centres such as Eleusis, Delphi and the island of Samothrace, and the discourse-communities of the Philosophers – the Neo-Platonists, Hermeticists and Gnostics who thrived in the late-classical world after the advent of Christianity and who pre-figured its rise. It is telling that classical paganism's most complete and (in scope) extensive theogonic text – the Dionysiaca of Nonnus of Persepolis in Egypt – was written by an author whose output later included a commentary on the christian Gospel of John. To understand this is to understand where the impetus for Christianisation was focussed in the less-literate climes of northwest Europe, such as Ireland, in the 5th/6thC CE.

Whereas some of our oldest surviving literature from the pagan world is religious, this aspect of the genre was in mortal decline in parallel to the rise in interest in philosophy and the 'mysteries' from the advent of the Hellenic period. By placing literacy in the hands of a few – a trained elite (after the model perhaps of the barbarian, Egyptian and Eastern peoples) – christianity would place itself at the heart of the new models of kingship appearing in the 'barbarian' world following the collapse of the Roman franchise in the west.

There are many similarities between the written medieval Irish myths and Greek legends. The reasons for this might be fourfold:

1. That the Irish believed in a shared widely-known and ancient cosmic worldview, populated with similar characters and themes to those of ancient Greece and southern Europe, and the Christian authors recorded this from traditional orally-transmitted narratives.

2. That literate monks used Greek and Roman (or Romano-British) myths to flesh out a written Irish narrative which did not otherwise exist – a kind of 'new age' eclecticism.

3. That Irish and Greek myths developed separately, yet shared similarities determined by (a) the culture and traditions/techniques of storytelling and (b) empirical reactions to natural phenomena.

4. A synthesis of points 1-3.

Obviously, the most likely answer is point 4 – we simply do not have enough evidence to support points 1-3 independently, but we have good evidence that all of them have been contributing explanations. I shall now present a number of Irish myths/mythic characters and their apparent Greco-Roman counterparts and let you decide for yourselves:

Cú Chulainn:

The archetypal indefatigable warrior super-hero of the 'Ulster Cycle' stories – Cú Chulainn – seems to have a particular similarity to Herakles or Hercules: He is the son of a god, associated with blacksmith-craftsmen (Cullain). Cullain seems to relate to the Greek 'earth-born' proto-blacksmiths known as the (Idaean) Dactyls, of whom Herakles was sometimes considered one. Cú was a supreme warrior, a lover of goddesses (Fand, wife of Manannán mac Lir) and his nemesis is a goddess (the Morrigan). He is a performer of fantastic tricks and sporting feats, yet forever tied to the whims of his king and his gods. He lives fast and dies young – a true aspect of the Celtic warrior ideal. Cú is also a 'king's champion' warrior archetype – a dog on a leash, as befits his name. He sometimes comes across as bombastic, brash, sometimes clumsy and insensitive – a bit of a lummox at times, and then at others, clever and dextrous, and light on his feet. Like Herakles, he travels to far-off islands and does battle with the weird as well as the mundane, performing 'feats' along the way.

One way in which Cú Chullain differs from Herakles is that Herakles was a folk-hero responsible for taming and conquering the wild and chaotic forces for the good of humanity. In the 'Ulster Cycle', Cú Chullain typically acts on behalf of the interests of his liege lord – like the other famous Greek warrior-strongman Achilles. This perhaps reflects the fact that these Irish legends (like their later French and British 'Arthurian' traditions) were often designed for telling at the courts of elite rulers, and therefore suited the value-system of this milieu. In folk-myths, Fionn and Cú Chullain often take on much more gigantic proportions and attributes.

The Battle of Maige Tuired:

This is the 'showdown' scene of the Irish mythological cycle stories in which the Tuatha Dé Danann, the Fir Bolg and the Fomorians are pitted against one another for supremacy of Ireland. The Fomoire are usually described as a race of sea giants in Irish mythology, and the Manx word Foawr (from 'Fomor') means 'Giant'. They seem similar to the aquatic Titans of Greek myth and the Cath Maige Tuired is like an Irish version of the Greek Titanomachy – the battle and overthrow of the Titans by the Olympian Gods, with whom the TDD share a certain similarity. Similar legends exist from Norse myth – the primal giants here are the Frost Giants: Titans at -40 Celsius! Of course, the bizarre cannibalistic and incestuous Greek narratives of the Titans are absent from the CMT and the 'Book of Invasions' stories which present more of a heroic pseudo-historical dynastic struggle. Tolkein borrowed heavily from the imagery of the battles of Maige Tuired in constructing his battle scenes in Lord of the Rings.

Giants and primordial helpers:

The landscape of Atlantic Europe – particularly those regions where Greco-Roman and later christian culture was slow to assert itself – is riddled with ancient mythology of primordial giants who supposedly played some important roles in determining the shape of the landscape – mountains, fjords, rivers, lakes, plains and great rocks. The same was true of the mythology of the Archaic period and Bronze Age of southern Europe – in particular the mythologies of ancient Greece, but we can discount these as playing a late originating role in the folklore of northern and northwestern legends due to the lack of impact of these material and cultural civilisations in these zones.

The Greek giants and Titans were 'Earth-Born' (Gygas – after Ge/Gaia, the personified Earth). The pagan Norse word used for giants in the middle ages was Gygr – existing into the more modern periods in the Scots Gyre and Faroese Gyro. The Manx equivalent of the Scots Brownie, Uirisk and Grogach legend was the Phynnodderee, 'Dooiney Oie' ('Night Man') or Glashtin – a being considered gigantic, primitive, coarse and animalistic in appearance who helped householders and warmed himself by the hearth at night when humans slept. His local legends seem, curiously, to conflate him with both Fionn mac Cumhaill and even Cú Chullain and, when not explicitly named, with the activities ascribed elsewhere in the Atlantic world to other giants – specified or unspecified. This is a representation of the archetypal earth-born ancestor, and is a particularly important and wide-ranging link between northern and southern pagan mythology which appears to have a commonality stretching way back into the Bronze Age. Herakles was also an aspect of this.

The Otherworld:

Both Greek and Irish myths portray the Otherworld as a location reachable by a westward journey over the great ocean. The legendary Greek islands of Elysium, the Hesperides/Erytheia and Ogygia, and the 'Islands of the Blessed' or 'Fortunate Isles' have their Irish equivalents in the many names of Gaelic mythology's magical western islands which were also considered the resort of departed souls: Mag Mell, Tír na nÓg, Tír na mBeo, Tír Tairngire, Tír fo Thuinn, Ildathach , Hy Brasil, Tech Duinn and Emain Ablach. These places are sometimes explicitly islands, sometimes under the sea, sometimes of a hybrid type that emerges (and just as soon disappears) from the sea.

Like in the Greek legends, the otherworld is also represented as a chthonic realm – beneath the earth. Like the Greeks, the Irish seem to have believed that the rivers of the world joined a 'world river', and that it re-manifested from the otherworld by piercing back though the earth as springs of water. Like the Greeks and Latins of southern Europe, and their fellow Bronze Age and Iron Age era 'Celtic' peoples further north and west they considered springs of water to be important and holy – no doubt for this reason. Sidhe mounds or Fairy Hills were the traditional 'home' of Irish (and to a lesser extent, Manx and Scottish fairies). They were sometimes considered to be the sources of rivers returning from the otherworld. Mountains and artificial mounds had similar associations in Ireland. In a flat landscape, a mound is something akin to an island – a consideration when addressing the 'otherworld inversion' belief that permeates Atlantic European folklore.

An interesting aspect of the Greco-Roman myth is how there seems to be a plasticity in portraying the otherworld 'places' (Elysium, for example) as both meadows or gardens and simultaneously as islands bordering Okeanos. This same conflation appears to represented quite strongly in the old Irish story 'The Voyage of Bran mac Febail' where he is conveyed to the otherworld islands over a sea which gradually appears to become a meadow.

Mermaids and Sirens:

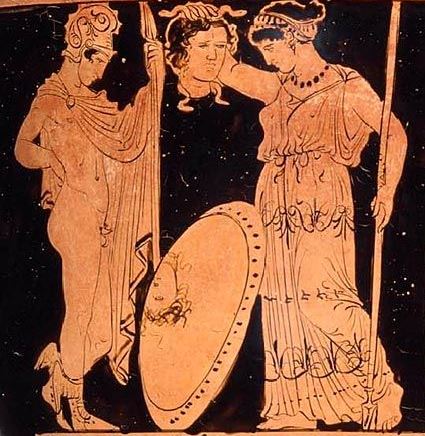

The idea of female (and male) entities who lured men to stay with them in the watery or otherworld realms are common to both Greek and Gaelic myths. The 'Sirens' occur in Greek myths such as Homer's Odyssey and the Argonautica ('Jason/Iason and the Argonauts'). They were sometimes depicted as half-bird, half-female inhabiting islands surrounded by huge rocks and high cliffs, luring sailors to their deaths on the treacherous shores with their beautiful songs. Calypso, the daughter of Atlas on Ogygia also fits the enchanting-island maiden archetype, and although was not considered one of the Sirenai, seems part of the same mythos. Even the Gorgons tempted brave Perseus to their realm, and from his 'killing' of Medusa there was a magical birth (of Pegasus and Chrysaor).

In Atlantic Celtic mythology, this function was the province of alluring beautiful mermaids – usually half-human, half-fish in their conception but sometimes 'seal people' (e.g. – Selkies). The Isle of Man's version of the Cailleach – Caillagh y Groamagh was supposed to fly in from the sea in the form of a bird at Imbolc/La'a Bride, and she may be another aspect of the beautiful fairy maiden called 'Tehi-Tegi' who in Manx legends lures men into the sea or a river to drown them, before flying away in the form of a wren (sometimes a bat!). The Gaelic (Irish/Gallovidian) Merrow was sometimes known as Suire which sounds very much like a version of 'Siren' although this may be in reference to known Greek myths, and this type of mermaid was associated with a feather hat or cape. Crofton Croker's 'Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland' is worth reading for a summary on the Merrows.

Harpies and Sidhe Gaoithe:

There was an explicit belief in former times in Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man that sudden gusts of wind were caused by the actions of spirits and fairies. Indeed, this was a feature of the demonology of medieval Christian Europe, and may well link back to the ancient Greek beliefs that the Harpies were responsible for the same. They were depicted (again) as half-woman, half bird or as winged female entities and were personifications of storm-winds. The Cailleach Bheara of the Scottish Highlands and Islands had a similar association, and was sometimes considered a female-avian who flapped her wings to make the winter storms. In the Isle of Man, the (not uncommon) tornados were sometimes supposed to be caused by a fairy known as Yn Gilley Vooar ny Gheay – 'Big Boy O' the Wind'.

River Nymphs and Sea Nymphs:

Perhaps subjoined to the mermaid legends, it is notable that the Greeks and the Irish personified their rivers with female spirits or entities. Evidence of this comes from the Dindseanchas legends and those of the so-called 'landscape-sovereignty' goddesses, otherwise referred to as Bean Sidhe, no doubt because river-drainage areas in mountainous landscapes tend to map and define territories. Greco-Roman mythology venerated such female water deities, and this tendency was also found in the European celtic world in the late Iron Age (although much of our evidence here comes after the period of Romanisation). Again, the 'Cailleach' personification from folklore seems to combine many of these functions (Harpies, Sirens, Nymphs etc) into the form of this single protean Titaness. Likewise, the Moura Encantada of the Iberian peninsula and the Marie Morgane of Brittany as well as the 'Lady of the Fountain' (or lake) of Arthurian lays and romances.

Summary:

It is apparent that ancient European paganism was a universal system of philosophy and 'science' illustrated through traditions of the arts: story, poetry, song, pictures, dances and drama. Every possible phenomenon seems to have been addressed by assigning mythology to it, and the boundary between the spiritual and the secular did not really exist – instead there was a continuum. The southern European civilisations emerging from the Bronze Age with a more oriental perspective, eventually coming to consider themselves 'better' and more 'enlightened' than their 'barbarian' cousins (and ancestors) in northeastern and northwest Europe, and due to warfare and incursions of these 'barbarians' between the 5thc BCE and the 1stC CE (and beyond), and due also to the dependence on written knowledge, a perception derived that their religious and spiritual beliefs were 'different', when in fact they had a shared root.