I have already mentioned in recent posts that there were legendary connections between the Atlantic Goddess and water: For starters she is represented in the constellation Orion, standing on the banks of the great white river of the Milky Way as it arches across the winter sky. As ‘Tehi Tegi‘ in the Isle of Man, she conveyed the souls of the dead across the land until they reached the rivers or the sea and were able to enter the realm of the Otherworld. The Cailleach traditions of Ireland, Scotland and Wales tell of her role in creating Lochs and other floods by neglecting to close off springs, and as the Bean Nighe she sat near water washing the garments and effects of the dead.. In Brittany she is represented by the oceanic fairy queen known as the ‘Gro’ach‘ and as a Moura Encantada in Portugal and Gallicia she is a guardian of springs. Archaeologists across Atlantic Europe recognise the association of springs with pagan goddess-worship.

It is perhaps unsurprising that the rivers of Ireland have associations with pagan female entities preserved in their legendary lore. A good example of such stories are from the onomastic explanations of placenames found in medieval literature, often produced by Christian monks. These texts – published in compiled form in the early 20thC as the ‘Metrical Dindshenchas‘ (taken from the mss. the Book of the Dun Cow, the Book of Leinster, the Rennes Manuscript, the Book of Ballymote, the Great Book of Lecan and the Yellow Book of Lecan) – has the following (from Vol.3) to say about the origin of the River Boyne (under ‘Boand 1’), the most prominent river of the Irish midlands, and one associated with a rich mythology and archaeology:

Sid Nechtain is the name that is on the mountain here,

the grave of the full-keen son of Labraid,

from which flows the stainless river

whose name is Boand ever-full.

Fifteen names, certainty of disputes,

given to this stream we enumerate,

from Sid Nechtain away

till it reaches the paradise of Adam.

Segais was her name in the Sid

to be sung by thee in every land:

River of Segais is her name from that point

to the pool of Mochua the cleric.

From the well of righteous Mochua

to the bounds of Meath’s wide plain,

the Arm of Nuadu’s Wife and her Leg are

the two noble and exalted names.

From the bounds of goodly Meath

till she reaches the sea’s green floor

she is called the Great Silver Yoke

and the White Marrow of Fedlimid.

Stormy Wave

from thence onward

unto branchy Cualnge;

River of the White Hazel

from stern Cualnge

to the lough of Eochu Red-Brows.

Banna is her name from faultless Lough Neagh:

Roof of the Ocean as far as Scotland:

Lunnand she is in blameless Scotland —

or its name is Torrand according to its meaning.

Severn is she called through the land of the sound Saxons,

Tiber in the Romans’ keep:

River Jordan thereafter in the east

and vast River Euphrates.

River Tigris

in enduring paradise,

long is she in the east, a time of wandering

from paradise back again hither

to the streams of this Sid.

Boand is her general pleasant name

from the Sid to the sea-wall;

The poet who wrote this account is effusive in his descriptions of the great river, comparing it (or perhaps more accurately actually identifying it) with the other great rivers of the known world, including the River Severn, the Tiber, the Tigris and Euphrates, the Jordan etc. It was believed that the oceans were made up of all the world’s rivers in the era of authorship – an idea born of classical antiquity and beyond. What is more important is the author implies that the river actually runs from Sid Nechtain to the ‘paradise of Adam’, being a direct allusion to a christianised telling of the pagan Irish belief in an Otherworld at the Ocean’s End, and to the Garden of Eden, where Christians believe life begins! This almost tells of a former belief in rebirth… The passage also implies that the river is regenerated from the East and returns to Sid Nechtain to flow again by some unspecified route.

Quite amazing.

The compiled texts go on to describe the mythological origin of the River of Boand:

I remember the cause whence is named

the water of the wife of Labraid’s son.

Nechtain son of bold Labraid whose wife was Boand, I aver;

a secret well there was in his stead,

from which gushed forth every kind of mysterious evil.

There was none that would look to its bottom

but his two bright eyes would burst:

if he should move to left or right,

he would not come from it without blemish.

Therefore none of them dared approach it

save Nechtain and his cup-bearers: —

these are their names, famed for brilliant deed,

Flesc and Lam and Luam.

Hither came on a day white Boand (her noble pride uplifted her),

to the well, without being thirsty to make trial of its power.

As thrice she walked round about the well heedlessly,

three waves burst from it, whence came the death of Boand.

They came each wave of them against a limb,

they disfigured the soft-blooming woman;

a wave against her foot, a wave against her perfect eye,

the third wave shatters one hand.

She rushed to the sea (it was better for her) to escape her blemish,

so that none might see her mutilation;

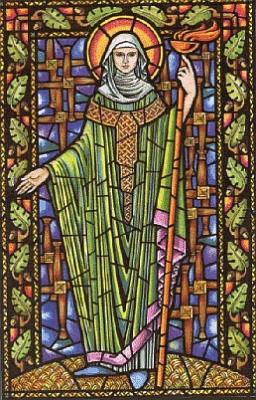

The authors relate a typical Irish Christian rescension of the pagan tale of the woman and the water. The passage also tells of the practice of circling a well or spring three times, which any folklorist who has studied Celtic traditions will recognise. The tale of Boand therefore acts on a number of levels: Firstly as a poetic figurative description of the river as a woman, secondly as descriptive account of the Boyne replete with onomastic and pseudo-historical details, and thirdly it seems to contain a warning to the ungodly of the fate which will meet them if they emulate the legendary magical female… Of particular interest is the manner in which the water harms Boand: It causes the ‘wounds’ of the Cailleach – the ‘fairy stroke’ of withering in one eye, one arm, one leg. Such ‘wounds’ are given to other magical females at rivers or fords or shorelines in other Irish myths from medieval works, including that of the Christian ‘St Brighid‘…

Medieval Irish tales with pagan themes usually contain a Christian footnote in their third part…