The ‘Hag of the Mill’ (Cailleach an Mhuilinn) is a mysterious and elusive character featured in a number of famous mythological tales from medieval Irish literature. This ‘grand dame’ appears variously as a helper, an adversary and a prophetess whose intervention determines the future outcomes of mythical narrative. Her ability to fly, leap and shape-shift marks her out as exceptional and supernatural – the very model of a goddess, in fact.

Mills were of course associated with ponds, lakes and water-courses, wind-powered mills not being known in ancient Ireland. They are therefore doubly associated with fertility and goodness, attaching a powerful aura of magical potency to them in folklore. The drudgery of hand-milling is also symbolic of the work of the lowly. Milling is both a destructive and creative act, and this is almost certainly why the Cailleach is associated with it in some Irish literary and folklore traditions.

The idea of magical females and fairies associated with mills was once apparently fairly widespread. As well as being a common theme in popular beliefs about witchcraft in the British Isles from at least the medieval period, it occurs in the Slavic myths of Baba Yaga (‘Mother Hag’), who was said to travel about with the aid of a magical mortar and pestle. The act of winnowing, hulling and grinding represents the uncovering and extraction of goodness: the revealing of what is hidden. The word ‘Cailleach’ (often translated as ‘hag’) means ‘veiled one’, and in the tales in which she appears, she often hides her inner nature, only to reveal it at critical junctures. The same can be said of Frau Holle or Holda and the Huldra figures of Germanic and Scandinavian folklore, whose name represents the same concept, demonstrating a deep and ancient conceptual link shared between Eurasian and European cultures. ‘Hulling’ is an english word for the act of removing the calyx covering a grain…

A set of ‘quern’ stones in a Viking era hand-mill. The grains were poured into the ‘eye’ of the mill and the stones rotated with a stick. Like the hearth of a house, the mill would have been associated with magical potency.

The ‘wheel’ of the millstone and the ‘wheel of the year’ share a common theme, represented in northern Europe’s ancient Great Goddess… Perhaps the popular ‘lucky’ holed stone used as an amulet is even a remnant of former Cailleach worship?

‘Lucky Stones’, also called ‘Hag Stones’ and ‘Witch Stones’: They are a familiar feature of folklore from across the British Isles and Ireland. A remnant of Cailleach worship?

In fact, the holed stone is also associated with the weights used on looms, and the weights used for fishing nets, so it represents a great deal of significance of nourishing and creative forces.

Holed stones and a necklace of glass beads and stones were among the grave goods of a pagan viking burial at Peel Castle in the Isle of Man.

With all of this in mind, I would now like to discuss the character of the ‘Mill Hag’ in context of a number of Irish myths surviving from the medieval period:

Compert Mongáin ocus Serc Duibe-Lácha do Mongán (‘The Conception of Mongan and Dub-Lacha’s Love for Mongan’)

The English text is here.

The fateful Cailleach threads her way repeatedly through this tale which essentially deals with the sovereignty of Ireland: First, as the ‘Caillech Dub’ or ‘Black Hag’ of Lochlann, she appears as a healer of kings by donating her magical cow to save the life of Eolgarg Mor, king of Lochlan, then as an instigator of conflict between the Ulster king Fiachna mac Baetán and Eolgarg. When things are going bad for Fiachna (Eolgarg unleashes a battalion of venemous sheep upon the Irish!) the god Manannán mac Lir appears to him an offers to save Fiachna’s army from the sheep upon the condition that he can go to Ireland disguised as Fiachna and beget a magical son upon Fiachna’s wife. In this manner is begat Mongan mac Fiachnae or ‘Mongan Fionn’, who Manannán fosters in his magical island kingdom in the west, teaching him the arts of magic and shape-shifting. After a period away, Mongan returns to Ireland replete with higher mystical knowledge and magical powers – a veritable incarnation of Manannan himself.

In the tale, Mongan and Dubh Lacha fall in love. However, she is betrothed to the King of Leinster and Mongan and his companion Mac an Daibh conspire to trick the king and rescue Dubh Lacha. They go to the Cailleach an Mhuilinn and ask for her help in their ruse, to which she gladly assents.

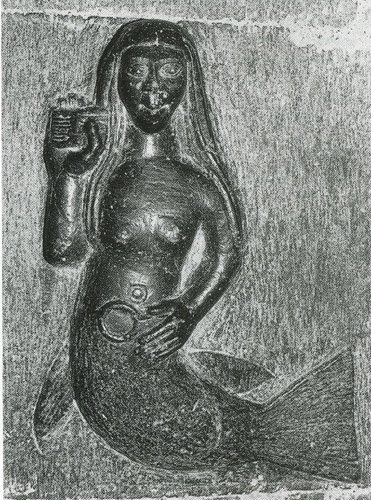

And in that way the year passed by, and Mongan and Mac an Daimh set out to the king of Leinster’s house. There were the nobles of Leinster going into the place, and a great feast was being prepared towards the marriage of Dubh-Lacha. And he vowed he would marry her. And they came to the green outside. ‘O Mongan,’ said Mac an Daimh, ‘in what shape shall we go?’ And as they were there, they see the hag of the mill, to wit, Cuimne. And she was a hag as tall as a weaver’s beam, and a large chain-dog with her licking the mill-stones, with a twisted rope around his neck, and Brothar was his name. And they saw a hack mare with an old pack- saddle upon her, carrying corn and flour from the mill.

And when Mongan saw them, he said to Mac an Daimh: ‘I have the shape in which we will go,’ said he, ‘and if I am destined ever to obtain my wife, I shall do so this time.’ ‘That becomes thee, O noble prince,’ [said Mac an Dairnh]. ‘And come, O Mac an Daimh, and call Cuimne of the mill out to me to converse with me.’ ‘It is three score years [said Cuimne] since any one has asked me to converse with him.’ And she came out, the dog following her, and when Mongan saw them, he laughed and said to her: ‘If thou wouldst take my advice, I would put thee into the shape of a young girl, and thou shouldst be as a wife with me or with the King of Leinster.’ ‘I will do that certainly,’ said Cuimne. And with the magic wand he gave a stroke to the dog, which became a sleek white lapdog, the fairest that was in the world, with a silver chain around its neck and a little bell of gold on it, so that it would have fitted into the palm of a man. And he gave a stroke to the hag, who became a young girl, the fairest of form and make of the daughters of theworld,to wit, Ibhell of the Shining Cheeks, daughter of the king of Munster. And he himself assumed the shape of Aedh, son of the king of Connaught, and Mac an Daimh he put into the shape of his attendant. And he made a shining-white palfrey with crimson hair, and of the pack-saddle he made a gilded saddle with variegated gold and precious stones. And they mounted two other mares in the shape of steeds, and in that way they reached the fortress.

Mongan uses his magic wand to transform the hag into a beautiful young woman who gets the king drunk and sleeps with him. Mongan and Dubh Lacha then make off. The next morning the king is found in bed with Cuimne – now transformed back into a gnarled hag, much to the dismay of his people. The theme is one of the king wedded to the sovereignty goddess, familiar from many other Irish tales, and as used in Chaucer’s ‘Wife of Bath’s Tale’. In the Mongan tale however, the beautiful maiden transforms into the hag – usually the reverse occurs: the brave hero kisses the hag, who transforms into a young beauty.

Interestingly, as well as identifying Mongan mac Fiachna with Manannan, the corpus of ‘Mongan’ literature also identifies him with the even more famous Fionn Mac Cumhaill, the trickster hunter-warrior-leader. Fionn’s dealings with the shapeshifting Fairy Queen and goddess of the earth, the Cailleach, are dealt with in the tale of ‘The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Grainne’:

Toruigheacht Diarmada agus Grainne (‘The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Grainne’):

The tale is ostensibly one of the love affair between Fionn’s wife Grainne, and his strapping young protege, Diarmuid. The two fall out violently and the narrative deals with the couple’s pursuit by Fionn, and the eventual death of Diarmuid. It is a tale of split loyalties and the tragedies of betrayal in love. The Cailleach’s appearance is as Fionn’s nursemaid, in Tir Tairngire – the Otherworld homeland of the Tuatha De Danann, and realm of Manannan. She agrees to help Fionn and attacks Diarmuid and Oscar, who are staying with Angus at the Brugh na Boyne.

The next morning Diarmuid and Oscar rose, and harnessed their fair bodies in their suits of arms of valor and battle, and those two mighty heroes went their way to the place of that combat, and woe to those, either many or few, who might meet those two good warriors when in anger. Then Diarmuid and Oscar bound the rims of their shields together that they might not separate from one another in the fight. After that they proclaimed battle against Finn, and then the soldiers of the king of Alba said that they and their people would go to strive with them first. They came ashore forthwith, and rushed to meet and to encounter them, and Diarmuid passed under them, through them, and over them, as a hawk would go through small birds, or a whale through small fish, or a wolf through a large flock of sheep; and such was the dispersion and terror and scattering that those good warriors wrought upon the strangers, that not a man to tell tidings or to boast of great deeds escaped of them, but all of them fell by Diarmuid and by Oscar before the night came, and they themselves were smooth and free from hurt, having neither cut nor wound. When Finn saw that great slaughter, he and his people returned out to sea, and no tidings are told of them until they reached Tir Tairngire (fairyland), where Finn’s nurse was. Finn came to her, and she received him joyfully. Finn told the cause of his travel and of his journey to the hag from first to last, and the reason of his strife with Diarmuid, and he told her that it was to seek counsel from her that he was then come; also that no strength of a host or of a multitude could conquer Diarmuid, if perchance magic alone might not conquer him. “I will go with thee,” said the hag, “and I will practise magic against him.” Finn was joyful thereat, and he remained with the hag that night; and they resolved to depart on the morrow.

Now it is not told how they fared until they reached the Brug upon the Boyne, and the hag threw a spell of magic about Finn and the fian, so that the men of Erin knew not that they were there. It was the day before that Oscar had parted from Diarmuid, and Diarmuid chanced to be hunting and chasing on the day that the hag concealed the fian. This was revealed to the hag, and she caused herself to fly by magic upon the leaf of a water lily, having a hole in the middle of it, in the fashion of the quern-stone of a mill, so that she rose with the blast of the pure- cold wind and came over Diarmuid, and began to aim at and strike him through the hole with deadly darts, so that she wrought the hero great hurt in the midst of his weapons and armor, and that he was unable to escape, so greatly was be oppressed; and every evil that had ever come upon him was little compared to that evil. What he thought in his own mind was, that unless he might strike the hag through the hole that was in the leaf she would cause his death upon the spot; and Diarmuid laid him upon his back having the Gae Derg in his hand, and made a triumphant cast of exceeding courage with the javelin, so that he reached the hag through the hole, and she fell dead upon the spot. Diarmuid beheaded her there and then and took her head with him to Angus of the Brug.

Although not explicitly referred to as ‘hag of the mill’, the narrative obviously invokes the ring-shaped grinding stone in its description of the curious leaf the Cailleach flies upon as she attacks Diarmuid. Another tale themes by flight and pursuit that features the Hag is:

Buile Shuibhne (‘Sweeney’s Frenzy’):

The full English text of this tale can be found here.

In the story, king Suibhne (‘Sweeney’), a 7thC pagan warlord of Dal nAraidhe, offends St Ronan Finn by tossing his psalter into a lake when the christian invader sets up a church on his lands without permission. This occurs just before the decisive Battle of Moira (Magh Ráth) of 637CE which was to mark the beginning of the ascendancy of the Uí Neill over the north of Ireland. In punishment for his anti-clerical transgressions, Suibhne is cursed by the saint with madness, and doomed to fly and leap across the landscape like a bird, never knowing the fate of his sons and kinsmen after the battle, at which the Dal nAraidhe were defeated. His final fate, Ronan tells him, is to eventually die pierced upon the point of a spear.

Suibhne subsequently lives like a bird, perching in trees and flitting from hilltop to hilltop, cursed to never wish for the comforts of settlement. His wild, bird-like condition is presented as lonely and tragic. Eventually he is captured by his kinsman Loingseachan (who is apparently also a miller), and he is restrained in chains so that he might live again among his people. With their care, his madness lifts temporarily, only to be robbed from him once more when he is entrusted one harvest-time to the care of Lonnog, the Hag of the Mill, who is described as Loingseachan’s mother in law, who challenges him to show his magical flying leaping ability, which she then reveals is also a faculty she herself posesses:

“… When Suibhne heard tidings of his only son, he fell from the yew, whereupon Loingseachan closed his arms around him and put manacles on him. He then told him that all his people lived; and he took him to the place in which the nobles of Dal Araidhe were. They brought with them locks and fetters to put on Suibhne, and he was entrusted to Loingseachan to take him with him for a fortnight and a month. He took Suibhne away, and the nobles of the province were coming and going during that time; and at the end of it his sense and memory came to him, likewise his own shape and guise. They took his bonds off him, and his kingship was manifest. Harvest-time came then, and one day Loingseachan went with his people to reap. Suibhne was put in Loingseachan’s bed-room after his bonds were taken off him, and his sense had come back to him. The bed-room was shut on him and nobody was left with him but the mill-hag, and she was enjoined not to attempt to speak to him. Nevertheless she spoke to him, asking him to tell some of his adventures while he was in a state of madness. ‘A curse on your mouth, hag!’ said Suibhne; ‘ill is what you say; God will not suffer me to go mad again.’ ‘I know well,’ said the hag, ‘that it was the outrage done to Ronan that drove you to madness.’ ‘O woman,’ said he, ‘it is hateful that you should be betraying and luring me.’ ‘It is not betrayal at all but truth,’; and Suibhne said:

Suibhne: O hag of yonder mill,

why shouldst thou set me astray?

is it not deceitful of thee that, through women,

I should be betrayed and lured?

The hag: Tis not I who betrayed thee,

O Suibhne, though fair thy fame,

but the miracles of Ronan from Heaven

which drove thee to madness among madmen.Suibhne: Were it myself, and would it were I,

that were king of Dal Araidhe

it were a reason for a blow across a chin;

thou shalt not have a feast, O hag.

‘O hag,’ said he, ‘great are the hardships I have encountered if you but knew; many a dreadful leap have I leaped from hill to hill, from fortress to fortress, from land to land, from valley to valley.’ ‘For God’s sake,’ said the hag, ‘leap for us now one of the leaps you used to leap when you were mad.’ Thereupon he bounded over the bed-rail so that he reached the end of the bench. ‘My conscience!’ said the hag, ‘I could leap that myself,’ and in the same manner she did so. He took another leap out through the skylight of the hostel. ‘I could leap that too,’ said the hag, and straightway she leaped. This, however, is a summary of it: Suibhne travelled through five cantreds of Dal Araidhe that day until he arrived at Glenn na nEachtach in Fiodh Gaibhle, and she followed him all that time. When Suibhne rested there on the summit of a tall ivy-branch, the hag rested on another tree beside him. It was then the end of harvest-time precisely. Thereupon Suibhne heard a hunting-call of a multitude in the verge of the wood. ‘This,’ said he, ‘is the cry of a great host, and they are the Ui Faelain coming to kill me to avenge Oilill Cedach, king of the Ui Faelain, whom I slew in the battle of Magh Rath.’ …”

This leaping hag is famous in Gaelic folklore as the earth-goddess Cailleach whose legendary jumps and falls created the landscape in folktales scattered across Scotland, Mann, Britain and Ireland. Once a pervasive goddess of northern Europe, her traditions have been corrupted so that she is variously depicted in corrupt and christianised myths as a giant, the devil or a great beast, even a horse. In some of this folklore, the Cailleach herself is said to manifest as a great bird (for instance, as the ‘Gyre Carline’ of Scottish lowland repute). She appears in the narrative of Buile Suibhne as the flying/leaping ‘mistress of the wilds’ who return Suibhne to his former sylvan madness – as if he was back-sliding from christian charity into paganism, which was still apparently strong among elements of the Dal nAraidhe and Picts of the 7thC.

During his flight with the Cailleach, Suibhne hears the first horns of the start of the stag-hunting season and fears that it is he who is hunted. He then utters a lay which identifies with the stags who rule the peaks of the hills, with the trees of the forest in which he alights, and draws parallels with both, describing the antlers as akin to the branches and thorns upon which he is cursed to alight, and these with Ronan’s prophesied fate for him to eventually die upon the point of a spear. He even refers t0 the Cailleach at one point as ‘mother of this herd’:

There is the material of a plough-team

from glen to glen:

each stag at rest

on the summit of the peaks.

Though many are my stags

from glen to glen,

not often is a ploughman’s hand

closing round their horns.

The stag of lofty Sliabh Eibhlinne,

the stag of sharp Sliabh Fuaid,

the stag of Ealla, the stag of Orrery,

the fierce stag of Loch Lein.

The stag of Seimhne, Larne’s stag,

the stag of Line of the mantles,

the stag of Cuailgne, the stag of Conachail,

the stag of Bairenn of two peaks.

O mother of this herd,

thy coat has become grey,

there is no stag after thee

without two score antler-points.

It is evident she (as an elder of his tribe) is showing him the fate of the stags pursued by the hunters to demonstrate to him that the ‘wild’ tribes of the pagans, attached to their hilltops and springs of water, are going to suffer the same fate. The other common folkloric motif associated with the Cailleach is as ‘mistress of herds and flocks’. Unable to bear her fatalistic taunting and her attempts to push him back into madness, he tricks the hag into leaping to her doom:

“… After that lay Suibhne came from Fiodh Gaibhle to Benn Boghaine, thence to Benn Faibhne, thence to Rath Murbuilg, but he found no refuge from the hag until he reached Dun Sobairce in Ulster. Suibhne leaped from the summit of the fort sheer down in front of the hag. She leaped quickly after him, but dropped on the cliff of Dun Sobairce, where she was broken to pieces, and fell into the sea. In that manner she found death in the wake of Suibhne …”

A similar fate came to the legendary hag Mal, who pursued the leaping Cuchullain to the Cliffs of Moher in a legend attached to Loop Head on the coast of County Clare. Evidently, the genesis of both stories lies within a more ancient pagan myth explaining how the landscape of Ireland was formed – possibly involving the chase of rutting stags, of which Cuchullain is a human representation. Patrick Weston Joyce (‘The Origin and History of Irish Names and Places’, Dublin, 1870) commented on a number of other places named after legendary leaps.

Why the ancient goddess manifests as the ‘Mill Hag’ is Buile Suibhne is still somewhat mysterious, indicating that the reader or listener was expected to know and understand why she manifests in such a rôle. Another tantalising hint at why this occurs is found in the conclusion of the story, in which Suibhne (like all good pagan heroes committed to the hands of Ireland’s christian mythographers) commits his last days to the care of Saint Mo Ling in Leinster, who was famed for his legendary water mill and whose name itself evokes the very word for Mill – Muillean – such that the anglicised version of his name is ‘Saint Mullins’. In fact, his legend states that the saint built a mile-long millrace connecting the river Barrow to his mill at Tighe Moling (now known as St Mullins). A hagiography (copied by one of the O’Clery brothers in the 17thC) contains accounts of his oratory being miraculously filled with grain, in order to pay the legendary Gobbán Saer (and his wife) who builds his houses and religious buildings at Teach Moling from the remains of the pagan Yew of Ross, said to have been felled by the Christian evangelists. Like the leaping Suibhne, Moling’s hagiography contains an episode in which he performs a series of leaps in order to confound and escape some evil spirits. How fitting, then that this saint would become the selfsame mad king’s guardian!

Students of the British traditions of Merddyn/Merlin discussed by Geoffrey of Monmouth will instantly be able to identify his own madness with the fate of Suibhne in the Irish story. The sylvan state of beast-like insanity and living among swine is a potent invocation of the pagan mysteries, except that in the christian narrative of Buile Suibhne the care and fate of Suibhne becomes dependent wholly upon the charity of saints Ronan Finn and Moling. Of the characters in Geoffrey’s Vita Merlini who might answer to that of the Irish/Scots/Manx Cailleach, the briefly-mentioned Morgen or Morgan who resides in a mystic island is the most likley candidate. She actually appears in the Martyrology of Donegal as a Saint, under the name Muirgen (‘Born of the Sea’) or Liban! In the ‘Sickbed of Cuchullain’ from the Ulster Cycle tales, ‘Liban’ is the sister of Manannan’s wife, Fand. Fionn mac Cumhaill’s nursemaid, indeed. Or maybe Mongan, or perhaps Manannan? Here is a translation of the entry:

MUIRGHEIN : i.e., a woman who was in the sea, whom the Books call Liban, daughter of Eochaidh, son of Muireadh ; she was about three hundred years under the sea, till the time of the saints, when Beoan the saint took her in a net, so that she was baptized, after having told her history and her adventures.