The belief in souls having an aerial or avian aspect is based upon the ancients’ elemental system of belief which put things of Air above the mundane world of Earth and Water in their scheme of the Universe – closer to the ‘upper’ stations occupied by Fire (which was believed to ascend above air) and Spirit (which was the ‘Ethereal’ aspect of Fire). Christian iconography today still uses the figurative portrayal of their ‘Holy Spirit’ as a dove coming down from the spiritual realms of heaven, but this idea has its roots deep in pagan ideaology (ie – natural philosophy).

Writing in Ireland during the 7thC CE, a monk known to scholars as ‘Augustine Hibernicus’ made a reference (in his exegetic writing known as De mirabilibus sacrae scripturae) ridiculing historic ‘magi’ (pagan priests) who once taught that the ancestral soul took the form of a bird. He argued that to give literal credence to the biblical miracle story of Moses and Aaron in Egypt which states that the wands of the Hebrew magicians were turned into actual serpents was:

`… et ridiculosis magorum fabulationibus dicentium in avium substantia majores suos saecula pervolasse, assensum praestare videbimur…’

`…to show assent to the ridiculous myths of the magi who say that their ancestors flew through the ages in the form of birds…’

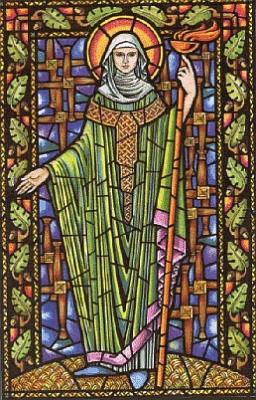

The context of this comment was against a political background where Christian authors and proselytes in Ireland (mostly monks related closely to clan chiefs) were still promoting stories about local saints such as Patrick, Brighid, Columba, Kevin, Senan etc. defeating ‘magical’ pagan adversaries in the early days of christianising Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man etc. For example, one of the adversaries of St Patrick in Tírechán’s 8thC account of his life was a flock of magical birds on Cruachán Aigli. Contemporary christianity was still struggling to come to terms with the fact that the biblical miracles it was trying to promote could not be reproduced to the sceptical (pagan-thinkers) who still transmitted fabulous magical tales of their own as part of the stylised traditional oral narrative about how the world was, and which undoubtedly formed an unassailable part of clan and community life. There was therefore an atmosphere of ‘anti-magic’ in the contemporary monkish discourse, but allowances made for magic in historical tales involving saints to show that for every action by a pagan character the Christian god would allow a greater and opposite reaction in order to destroy paganism once and for all.

This Irish theme of birds representing fairies or souls of ancestors (as ‘fallen angels’) appears later in a modified form in one of the most popular European books of the high middle ages – the Legenda Aurea (Golden Legend) of James/Jacob of Voraigne (c.1260). This collection of stories in Latin about saints was drawn from traditions across Europe and of particular interest is the popular Irish hagiography of St Brendan, postulated to be a christianisation of the apparently pagan tale of the voyage of Bran mac Febal to the otherworld. In the Brendan tale, the saint is addressed by a flock of birds (here translated from the Latin):

“…And then anon one of the birds fled from the tree to Saint Brandon, and he with flickering of his wings made a full merry noise like a fiddle, that him seemed he heard never so joyful a melody. And then Saint Brendon commanded the bird to tell him the cause why they sat so thick on the tree and sang so merrily ; and then the bird said: Sometime we were angels in heaven, but when our master Lucifer fell down into hell for his high pride, we fell with him for our offences, some higher and some lower after the quality of the trespass, and because our trespass is but little, therefore our Lord hath set us here out of all pain, in full great joy and mirth after his pleasing, here to serve him on this tree in the best manner we can…”

The birds are recounting to Brendan a version of a belief that became common across Europe after the spread of christianity, and that was applied in dealing with pagan indigenous spirits from Iceland and Orkney (Hulderfolk) through to Slavic Russia (Domovoi etc): This was that these spirits, beloved of the people, were really fallen angels from that (confused) Christian interpretation of the biblical narrative (Isaiah 14:12) about a character called ‘Morning Star’ (‘Lucifer’) and his ‘fall’ from grace. This sole reference in the Jewish religious books is used by christians to suppose that the angel Satan (God’s right-hand man in the Book of Job) was ‘Lucifer’ who fell from heaven with his rebel angels after challenging the monotheistic god. Jews don’t believe this, saying that the passage is about a human ruler punished for his pride. The Christian interpretation was designed to incorporate and find a place for recidivist (probably ‘pre-Olympian’) indigenous European beliefs: of genii and daemones, and in ancestral domestic spirits in the new Christian order. It paints them as evil representatives of an adversarial christian anti-god called ‘Satan’, who appears as god’s most important angel-servant in the semitic Old Testament stories, and arguably in the same context in the Gospel of Matthew (4:9).

‘Augustine Hibernicus’ and James/Jacob of Voraigne both appear to be quoting from or referring to the same tradition of folkore that remembered the old beliefs. This legend existed in Ireland and the Isle of Man in the late 19thC. Manx folklorist William Cashen wrote the following of it (‘William Cashen’s Manx Folk-Lore’, Pub. Johnson, Douglas 1912):

“…The Manx people believed that the fairies were the fallen angels, and that they were driven out of heaven with Satan. They called them “Cloan ny moyrn”: The Children of the pride (or ambition) (Ed: May be a corruption of Cloan ny Moiraghyn – see later). They also believed that when they were driven out of heaven they fell in equal proportions on the earth and the sea and the air, and that they are to remain there until the judgment…”

And Lady Wilde said ( ‘Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms and Superstitions of Ireland’, p.89 1888):

“…all the Irish, believe that the fairies are the fallen angels who were cast down by the Lord God out of heaven for their sinful pride. And some fell into the sea, and some on the dry land, and some fell deep down into hell, and the devil gives to these knowledge and power, and sends them on earth where they work much evil. But the fairies of the earth and the sea are mostly gentle and beautiful creatures, who will do no harm if they are let alone, and allowed to dance on the fairy raths in the moonlight to their own sweet music, undisturbed by the presence of mortals…”

This belief was common to many other countries besides, from the Atlantic to the Baltic. The fairy multitude was the ‘Sluagh Sidhe’ or ‘Fairy Host’ – represented in Irish, Manx, Welsh and Scots folklore as a tumultuous aerial flock who might carry people aloft on wild rides, and that caused whirlwinds and bad weather through their aerial battles. They also caused sickness and disease.

Walter Evans-Wentz’s ‘The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries’ was a compendium of fairy lore collected around the turn of the 20th century collected with the assistance of a group of prominent folklorists from throughout the Celtic provinces. He collected the following account of the Sluagh Sidhe from a woman named Marian MacLean (nee MacNeil) of Barra (pp.108-110):

‘…Generally, the fairies are to be seen after or about sunset, and walk on the ground as we do, whereas the hosts travel in the air above places inhabited by people. The hosts used to go after the fall of night, and more particularly about midnight. You’d hear them going in fine. weather against a wind like a covey of birds. And they were in the habit of lifting men in South Uist, for the hosts need men to help in shooting their javelins from their bows against women in the action of milking cows, or against any person working at night in a house over which they pass. And I have heard of good sensible men whom the hosts took, shooting a horse or cow in place of the person ordered to be shot…

… My father and grandfather knew a man who was carried by the hosts from South Uist here to Barra. I understand when the hosts take away earthly men they require another man to help them. But the hosts must be spirits, My opinion is that they are both spirits of the dead and other spirits not the dead.’

Wentz then goes on to comment:

The question was now asked whether the fairies were anything like the dead, and Marian hesitated about answering. She thought they were like the dead, but not to be identified with them. The fallen angel idea concerning fairies was an obstacle she could not pass, for she said, ‘When the fallen angels were cast out of Heaven God commanded them thus:–“You will go to take up your abodes in crevices under the earth in mounds, or soil, or rocks.” And according to this command they have been condemned to inhabit the places named for a certain period of time, and when it is expired before the consummation of the world, they will be seen as numerous as ever.’

Again, we can see a tantalising expression of ancient traditions that Wentz found his modern narrator having difficulty fully reconciling in her own mind, although she quotes the catechism about fairies as fallen angels as if it were a passage from the bible!

Alexander Carmichael (Carmina Gaedelica 2 pp.330-331) was more explicit than Wentz when speaking through his Hebridean sources, some of whom he no doubt introduced to Wentz: (Ed note: my emphasis added)

Sluagh – ‘Hosts’, the spirit world – the ‘hosts’ are the spirits of mortals who have died. The people have many curious stories on this subject. According to one informant, the spirits fly about “n’an sgrioslaich mhor, a sios agusa suas air uachdar an domhain mar na truidean’ – ‘In great clouds, up and down the face of the world like the starlings, and come back to the scenes of their earthly transgressions’. No soul of them is without the clouds of earth, dimming the brightness of the works of God, nor can any make heaven until satisfaction is made for the sins on earth. In bad nights, the hosts shelter themselves, ‘ fo gath chuiseaga bheaga ruadha agus bhua-ghallan bheaga bhuidhe’ –

‘behind little russet docken stems and little yellow ragwort stalks’.They fight battles in the air as men do on the earth. They may be heard and seen on clear frosty nights, advancing and retreating, retreating and advancing, against one another. After a battle, as I was told in Barra, their crimson blood may be seen staining rocks and stones. ‘Fuil nan sluagh’, the blood of the hosts is the beautiful red ‘crotal’ of the rocks, melted by frost. These spirits used to kill cats and dogs, sheep and cattle, with their unerring venemous darts. They commanded men to follow them, and men obeyed, having no alternative.

It was these men of earth who slew and maimed at the bidding of their spirit-masters, who in return ill-treated them in a most pitiless manner. ‘Bhiodh iad ’gan loireadh agus ’gan loineadh agus ’gan luidreadh anus gach lod, lud agus lon’–They would be rolling and dragging and trouncing them in mud and mire and pools. ‘There is less faith now, and people see less, for seeing is of faith. God grant to thee and to me, my dear, the faith of the great Son of the lovely Mary.’ This is the substance of a graphic account of the ‘sluagh,’ given me in Uist by a bright old woman, endowed with many natural gifts and possessed of much old lore. There are men to whom the spirits are partial, and who have been carried off by them more than once. A man in Benbecula was taken up several times. His friends assured me that night became a terror to this man, and that ultimately he would on no account cross the threshold after dusk. He died, they said, from the extreme exhaustion consequent on these excursions. When the spirits flew past his house, the man would wince as if undergoing a great mental struggle, and fighting against forces unseen of those around him. A man in Lismore suffered under precisely similar conditions. More than once he disappeared mysteriously from the midst of his companions, and as mysteriously reappeared utterly exhausted and prostrate. He was under vows not to reveal what had occurred on these aerial travels…

… The ‘sluagh’ are supposed to come from the west, and therefore, when a person is dying, the door and the windows on the west side of the house are secured to keep out the malicious spirits. In Ross-shire, the door and windows of a house in which a person is dying are opened, in order that the liberated soul may escape to heaven. In Killtarlity, when children are being brought into the world, locks of chests and of doors are opened, this being supposed, according to traditional belief, to facilitate childbirth.

The West is, of course, the direction of the setting sun and supposed location of the ‘Blessed Isles’ (which go under a variety of euphemistic names) where the dead live in ancient Atlantic/Celtic folklore and legend. Carmichael’s account of the Hebridean idea of the Sluagh draws together the widespread references from throughout the Celtic world of fairies in an aerial state: Riding plant stalks through the air, causing illness by darts and diseased blasts of wind and carrying the living spirits of humans aloft, enslaving them to their bidding.

The connection between birds and spirits also occurs in the Irish and Manx wren legends and wren-hunts, also as the Morrigan-Badbh of Irish folklore and legend, and in the form of the Manx Caillagh ny Groamagh (a personification of winter and storms just like the highland Cailleach) who supposedly comes ashore from the oceans on St Bridget’s day in the form of a great bird before transforming into an old woman (Caillagh/Cailleach) who looks to kindle a fire. In southern Scotland during the 16thC this fearsome legendary female was referred to as the ‘Gyre Carline’ – the bird-form of the ‘Cailleach Vear’ legendary female figure of the Highlands, and once at the centre of the Celtic/Atlantic religious mythos as I shall later attempt to prove. In fact, the association between the Cailleach Vear/Bhear/Beara (and the multiplicity of other names she appears under) and flocks or hosts of animals is explicit in ancient Scottish traditions. In the Isle of Man she was sometimes also known as ‘Caillagh ny Fedjag’ (‘Old Woman of the Feathered Ones’ or ‘Old Woman of the Whistlers’) and was sometimes imagined as a giant whose presence could be witnessed in swirling flocks of birds, such as crows, starlings and plovers. Her name (and gender) became corrupted to Caillagh ny Faashagh in Sophia Morrison’s book of Manx Fairy Tales. Another Manx folklorist – W.W.Gill – said (A Manx Scrapbook, Arrowsmith, 1929) that fairies were known by the term Feathag. All seemingly related to a core idea – first referred to by ‘Augustine Hibernicus’ – that ancestral spirits have an aerial presence…

Going back much further in time to Iron Age Europe, we must remember that the Augurs and Haruspices of ancient Rome (originally Etruscan in their foundation) were priests and officials whose job it was to watch the behaviour and flight of birds in order to determine the will of the divine, so we can see that there is an entrenched ancient belief about spiritual forces being represented by birds in ancient Europe. Medieval Anglo-Saxons and Scandinavians applied similar superstitious import to the calls, flight and behaviour of members of the crow family…

The ‘Hidden Folk’:

The other theme in Atlantic fairy belief is the idea of them as (ancestral) spirits hidden away after the coming of christianity. The Icelandic Huldufólk, Orcadian Hulder-folk, and the fairy children of Germanic folklore’s Huldra/Holde/Hylde female personages have their equivalent versions in the legends of the Atlantic celts: A prime example of this, and one that also ties in to the souls-as-birds theme, is the great medieval Irish story of ‘The Children of Lir’ which occurs in a modified form in the writings of the christianised pseudo-history of Ireland: the ‘Book of Invasions’ or Lebor Gabála Érenn as well as in the text called Acallam na Senórach. These tell of a group of children (adopted or otherwise) of an ancestral heroic figure, sometimes turned into swans (or fish), and destined to wonder or hide in this form for many ages until released by a christian agency, depending on the telling.

Interestingly, the Valkyries of Norse folklore (conductors of the souls of the battle-dead) appear as swan-maidens in some tellings… Even in Wales, a form of the legend exists, and author William Wirt-Sikes reported the following one from Anglesey in the late 1800’s (‘British Goblins: Welsh Folk-Lore, Fairy-mythology, Legends and Traditions’, Pub: London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington, 1880):

“…In our Savior’s time there lived a woman whose fortune it was to be possessed of nearly a score of children, and as she saw our blessed Lord approach her dwelling, being ashamed of being so prolific, and that he might not see them all, she concealed about half of them closely, and after his departure, when she went in search of them, to her great surprise found they were all gone. They never afterwards could be discovered, for it was supposed that as a punishment from heaven for hiding what God had given her, she was deprived of them; and it is said these her offspring have generated the race called fairies…”

All of these types of legend or folktale (Aarne-Thompson-Uther type 758) often refer back to the ‘hidden’ elves/fairies/subterraneans (the souls of the dead) as children of a particular impoverished female, in order to suit a euhemerised christian narrative.