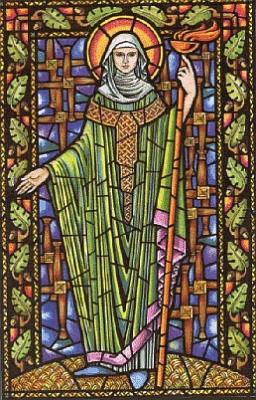

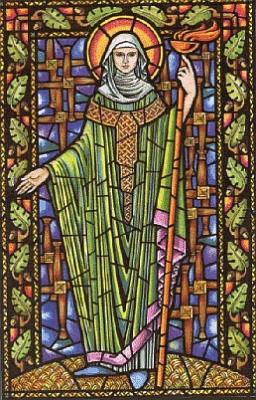

Bride, Brighid, Brigit, Bridget and Brigte – all names of this important Irish holy figure linked to Kildare and generally supposed to have been active in the 5th and 6th centuries coeval with the mission of Patrick. She was contemporary to the early (more accurately post-Patrician) christianising process in Ireland and there are very cogent theories that she was a Christianisation of a pagan Goddess, which I intend to explore.

One of the earliest written records we have of her in the Irish language is a hagiographical text composed by unknown monks during the 9th century, based on the earlier Latin texts, and copied into manuscript collections by Abbeys and collectors: This is known as ‘Bethu Brigte’ (from Oxford University: MS Rawlinson B 512). It is full of magical details and is obviously designed to portray Brigit as an ally and contemporary of Patrick, a fact missing from the older Latin hagiographies….

I have reproduced here the CELT translation, taken from: Bethu Brigte. Donnchadh Ó hAodha (ed), First edition. Pub. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1978) … with my own interlineal notes for your interest… (please note that the start and end of the original text are incomplete;)

1

. . .The miracles were published abroad. One day in that place Broicsech went to milk and she leaves nobody in her house except the holy girl who was asleep. They saw that the house had caught fire behind them. The people run to its aid, thinking that they would not one house-post against another. The house is found intact and the girl asleep and her face like . . . And Brigit is revered [there] as long as it may exist (?).

AP: The name of Brigit’s mother: Broicsech may be a derived from the act of pot-cooking, as befits her position as a slave. The source of the fire would be the hearth of the house, the focus of influence for a pagan goddess. The presence of a ‘sacred hearth’ that was never allowed to be extinguished, along with a sacred meadow, and a sacred enclosure that no man could pass were observations of the saint’s sanctuary at Kildare made by Giraldus Cambrensis during the 12th century, following the Anglo-Norman invasions. The Niamhog of Inniskea was an ‘idol’ reverenced by the islanders as late as the 19th century, and it was supposed to protect a house from fire.

2

On a certain day the druid was asleep and he saw three clerics wearing white hooded garments baptizing (the above-mentioned) Brigit, and one of the three said to him, ‘Let Brigit be your name for the girl.’

AP: The ‘three men in white’ are implied to be Patrick and his attendants, echoing the description of Tirechan in the Book of Armagh: The text claims that God wants the girl to be given the pagan name Brigit.

3

The druid and the female slave and her child were at Loch Mescae, and the druid’s mother’s brother was there too; the latter was a Christian. When they were there at midnight the druid was watching the stars and he saw a fiery column rising out of the house, from the precise spot where the slave and her daughter were. He woke his mother’s brother and he saw it also, and the latter said that she was a holy girl. ‘That is true’, said he, ‘if I were to relate to you all her deeds.’

AP: These Christian slaves are probably British in origin, gained by the raids by the Irish on sub-Roman Wales, England and Scotland. The text describes Brigit’s father – a druid/magus – watching the stars and making auguries, and gives validity to these powers as they proclaim the girl as a Christian saint! The druid and his uncle appear to begin to convert their beliefs…

4

On another occasion when the druid and his mother’s brother were in a house and the girl asleep, wherever her mother was, they heard the low voice of the girl in the side of the house, and she had not yet begun to speak. ‘Look for us’, said the druid to his maternal uncle, ‘how our girl is, for I do not dare to do so since I am not a Christian.’ He saw her lying in a crossvigil and she was praying. ‘Go again’, said the druid, ‘and ask her something this time, for she will say something to you now.’ He goes and addressed her. ‘Say something to me, girl’, said he. The girl then spoke two words to him: ‘This will be mine, this will be mine.’ The maternal uncle of the druid did not understand that. ‘Reveal [it] to us’, said he to the druid, ‘for I do not understand [it].’ ‘You will be very displeased with it’, said the druid. ‘This is what she has said’, said the druid, ‘this place will be hers till the day of doom.’ The maternal uncle of the druid shrank for the idea of (?) Brigit’s holding the land. The druid said, ‘Truly it shall be fulfilled. This place will be hers although she go with me to Munster’.

AP: Another vision of the future to the figurative pagan father, Dubthach (a name used as a hypostasis for similar characters in other early Irish Christianisation narratives). Brigit (the daughter of a slave, not supposed to inherit) claims the land of her father (an tribal leader or aristocrat)… ‘This to me’ (or its Irish and Manx equivalents) were the words supposedly spoken by well- and field-skimming witches in 19thC folklore accounts!

p.21

5

When it was time to wean her the druid was anxious about her; anything he gave her [to eat] she vomited at once, but her appearance was none the worse. ‘I know’, said the druid, ‘what ails the girl, [it is] because I am impure.’ Then a white red-eared cow was assigned to sustain her and she became well as a result.

AP: A curious syncresis – fairy or otherworld animals were supposed to be white with red ears in ancient Irish folklore! This passage appears to represent Brigit’s need for spiritual sustenance. The authors appear to make no difference between the Christian heaven and the Irish Otherworld in this interesting passage.

6

Thereafter the druid went to Munster, to be precise into Úaithne Tíre. There the saint is fostered. After a time she says to her fosterer: ‘I do not desire to serve here, but send me to my father, where he may come to meet me.’ This was done and her father Dubthach brought her away to his own patrimony in the two plains of Uí Fhailgi. She remained there among her relatives, and while still a girl performed miracles.

AP: This passage appears to show that Brigit and her father were more powerful than her fosterer, and perhaps simply exists to reinforce a historic primacy. It is she that decides that she does not wish to be fostered at this location (perhaps because it was anti-Christian?).

7

Then she was taken to a certain virgin to be fostered by her. It is Brigit who was cook for her afterwards. She used to find out the number of guests that would come to her fostermother, and whatever the number of guests might be the supply of bread did not fail them during the night.

AS: This passage again evokes the spiritual power of fecundity of the hearth that Brigit represents, a position that appears to be a pagan attribution to the Goddess.

8

Once her fostermother was seriously ill. She was sent with another girl to the house of a certain man named Báethchú to ask for a drink of ale for the sick woman. They got nothing from Báethchú . . . They came to a certain well. She brought three vessels’ full therefrom. The liquid was tasty and intoxicating, and her fostermother was healed immediately. God did that for her.

AP: She changes water from a spring well (a pagan theme) into wine (a Christian one). Alcoholic beverages were the safest drink, and therefore most suitable for the sick.

9

One day Dubthach made her herd pigs. Robbers stole two of the boars. Dubthach went in his chariot from Mag Lifi and he met them and recognized his two boars with them. He seizes the robbers and bound a good mulct for his pigs on them. He brought his two boars home and said to Brigit: ‘Do you think you are herding the pigs well?’ ‘Count them’, said she. He counts them and finds there numbers complete.

AP: She is without reproach by a pagan druid! Dubthach fines the robbers, but he apparently has no right to this ‘tithe’ as God has made sure his fine was unlawful… This is an indictment of the pagan leader.

10

On a certain day a guest came to Dubthach’s house. Her father entrusted her with a flitch of bacon to be boiled for the guest. A hungry dog came up to which she gave a fifth part of the bacon. When this had been consumed she gave another [fifth]. The guest, who was looking on, remained silent as though he was overcome by sleep. On returning home again the father finds his daughter. ‘Have you boiled the food well?’, said her father. ‘Yes’, said she. And he himself counted [them] and found [them intact]. Then the guest tells Dubthach what the girl had done. ‘After this’, said Dubthach, ‘she has performed more miracles than can be

p.22

recounted.’ This is what was done then: that portion of food was distributed among the poor.

AP: The Druid begins to practice Christian charity!

11

On another occasion after that an old pious nun who lived near Dubthach’s house asked Brigit to go and address the twenty-seven Leinster saints in one assembly. It was just then that Ibor the bishop recounted in the assembly a vision which he had seen the night before. ‘I thought’, said he, ‘that I saw this night the Virgin Mary in my sleep, and a certain venerable cleric said to me: ‘This is Mary who will dwell among you’.’ Just then the nun and Brigit came to the assembly. ‘This is the Mary who was seen by me in a dream.’ The people of the assembly rose up before her and went to converse with her. They blessed her. The assembly was held where now is Kildare, and there Ibor the bishop says to the brethren: ‘This site is open to heaven, and it will be the richest of all in the whole island; and today a girl, for whom it has been prepared by God, will come to us like Mary.’ It happened thus.

AP: This is the passage which appears to give credence to the conflation of Brigit with Mary. She became known as the ‘Mary of Ireland’ or ‘Mary of the Gael’ (Carmichael). It is probable that ‘Mary’ refers to ‘Berry’, ‘Beara’, ‘mBoire’, ‘Muire’, ‘Morrigan’, ‘Mourie’ etc – epithets of the Goddess which survived in folklore.

12

Another time thereafter she wished to visit her mother who was in slavery in Munster, and her father and fostermother would scarcely allow her to go. She went however. Her mother was at that time in . . . engaged in dairy work away from the druid, and she was suffering from a disease of the eye. Brigit was working in her stead, and the druid’s charioteer was herding the cattle; and every churning she made, she used to divide the produce into twelve portions with its curds, and the thirteenth portion would be in the middle and that was greater than every other portion. ‘Of what advantage to you deem that to be?’, said the charioteer. ‘Not hard’, said Brigit. ‘I have heard that there were twelve apostles with the Lord, and he himself the thirteenth. I shall have from God that thirteen poor people will come to me one day, the same number as Christ and his apostles.’ ‘And why do you not store up some of the butter?’ said the charioteer, ‘for that is what every dairy-worker does.’ ‘It is difficult for me’, said Brigit, ‘to deprive Christ of his own food.’ Then baskets were brought to her to be filled from the wife of the druid. She had only the butter of one and a half churnings. The baskets were filled with that and the guests, namely the druid and his wife, were satisfied. The druid said to Brigit: ‘The cows shall be yours and let you distribute the butter among the poor, and your mother shall not be in service from today and it shall not be necessary to buy her, and I shall be baptized and I shall never part from you.’ ‘Thanks be to God’, said Brigit.

AP: Women’s work, again! This description of dairying applies to the old principle of the ‘baker’s dozen’ in bread-making but applied to making butter: Fascinatingly it was still a practice of dairying women in the Isle of Man into the 20th century, would always place a pat of butter from the churning on the wall of the dairy ‘for the fairies’. Butter was a vital part of the diet in the Atlantic world – high rainfall and warmer oceanic climates made Ireland and Mannin prime dairying regions. SOfar, Brigit’s work is that of a young woman: minding the hearth, cooking, fetching water, making beer, milking, making butter. The druid frees her mother from servitude, gives her the freedom of her cattle (the goddess at Beltain), and agrees to be baptized. The story now enters another phase in the ‘three ages of woman’…

13

On one occasion Dubthach brought Brigit to the king of Leinster, namely Dúnlang, to sell her as a serving slave, because her stepmother

p.23

had accused her of stealing everything in the house for clients of God. Dubthach left her in his chariot to mind it on the green of the fort and he leaves his sword with her. She gave it to a leper who came to her. Dubthach said to the king: ‘Buy my daughter from me to serve you, for her manners have deserved it.’ ‘What cause of annoyance has she given?’, said the king. ‘Not hard’, said Dubthach. ‘She acts without asking permission; whatever she sees, her hand takes.’ Dubthach on returning questions her about that precious sword. She replied: ‘Christ has taken it.’ Having learned that, he said: ‘Why, daughter, did you give the value of ten cows to a leper? It was not my sword, but the king’s.’ The girl replied: ‘Even if I had the power to give all to Leinster, I would give it to God.’ For that reason the girl is left in slavery. Dubthach returned to his home. Wonderful to relate, the virgin Brigit is raised by divine power and placed behind her father. ‘Truly, Dubthach’, said the king, ‘this girl can neither be sold nor bought.’ Then the king gives a sword to the virgin, and . . .After the afore-mentioned miracles they return home.

AP: It comes time to place her into service… The King of Leinster recognises Brigit’s holiness and returns her to her father along with a replacement sword (a gift of nobility placed in her hands).

14

Shortly afterwards a man came to Dubthach’s house to woo Brigit. His name was Dubthach moccu Lugair. That pleased her father and her brothers. ‘It is difficult for me’, said Brigit, ‘I have offered up my virginity to God. I will give you advice. There is a wood behind your house, and there is a beautiful maiden [therein]. She will be betrothed to you, and this is how you will recognize it: You will find an enclosure wide open and the maiden will be washing her father’s head and they will give you a greater welcome, and I will bless your face and your speech so that whatever you say will please them.’ It was done as Brigit said.

AP: Brigit rejects the pagan prince, but arranges a satisfactory marriage for him. This is allegorical for the power of the church in shaping temporal power and alliance.

15

Her brothers were grieved at her depriving them of the bride-price. There were poor people living close to Dubthach’s house. She went one day carrying a small load for them. Her brothers, her father’s sons, who had come from Mag Lifi, met her. Some of them were laughing at her; others were not pleased with her, namely Bacéne, who said: ‘The beautiful eye which is in your head will be betrothed to a man though you like it or not.’ Thereupon she immediately thrusts her finger into her eye. ‘Here is that beautiful eye for you’, said Brigit. ‘I deem it unlikely’, said she, ‘that anyone will ask you for a blind girl.’ Her brothers rush about her at once save that there was no water near them to wash the wound. ‘Put’, said she, ‘my staff about this sod in front of you.’ That was done. A stream gushed forth from the earth. And she cursed Bacéne and his descendants, and said: ‘Soon your two eyes will burst in your head.’ And it happened thus.

AP: This passage is an important recognition of the ‘Cailleach’ figure which Brigit was to replace: she loses one eye rather, becoming alike to the poets’ representation of the Hag. She also creates a spring well from the earth at the point of this act – wells were closely linked to cures for the eyes in ancient Atlantic folklore. The clarity of water and the clarity of the healthy eye were linked, and the ‘Evil Eye’ is a thing of envy (or even love and lust) – for this reason Brigit plucks out her own eye in this passage.

p.24

16

Dubthach said to her: ‘Take the veil then, my daughter, for this is what you desire. Distribute this holding to God and man.’ ‘Thanks be to God’, said Brigit.

AS: The parent finally accepts the new vocation.

17

On a certain day she goes with seven virgins to take the veil to a foundation on the side of Cróchán of Bri Éile, where she thought that Mel the bishop dwelt. There she greets two virgins, Tol and Etol , who dwelt there. They said: ‘The bishop is not here, but in the churches of Mag Taulach.’ While saying this they behold a youth called Mac Caille, a pupil of Mel the bishop. They asked him to lead them to the bishop. He said: ‘The way is trackless, with marshes, deserts, bogs and pools.’ The saint said: ‘Extricate us [from our difficulty].’ As they proceeded on their way, he could see afterwards a straight bridge there.

AP: This is an expression of Brigit as one who guides lost travellers. Manx fishermen used to cast the palatal bone of the Bollan Wrasse to achieve such an augury – this was probably one of the oceanic forms associated with the goddess: it was a fish who tended the wrack. The ‘veil’ as well as the name ‘Mac Caille’ reminds us of the Cailleach. The Manx word for ‘veil’ or ‘covering’ is Breid. Bride. Brighde. Brigit….

18

The hour of consecration having arrived, the veil was raised by angels from the hand of Mac Caille, the minister, and is placed on the head of saint Brigit. Bent down moreover during the prayers she held the ash beam which supported the altar. It was afterwards changed into acacia, which is neither consumed by fire nor does it grow old through centuries. Three times the church was burned down, but the beam remained intact under the ashes.

AP: Mac Caille may be the same character as the Manx saint ‘Maughold’. The Isle of Man had a nunnery dedicated to St Brigid and its 12thC Viking king was involved with the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland during which there was a translation and centralisation of relics of the patron saints of Ireland: Patrick, Brigid and Colmcille… There is another reference in this passage to resistance to fire, and the local Ash beam is converted to (fireproof) Acacia – a Middle-Eastern or African tree, described in the Bible (Exodus) as the material employed in the construction of the tabernacle and its shrines, hence the use here.

19

The bishop being intoxicated with the grace of God there did not recognise what he was reciting from his book, for he consecrated Brigit with the orders of a bishop. ‘This virgin alone in Ireland’, said Mel, ‘will hold the Episcopal ordination.’ While she was being consecrated a fiery column ascended from her head.

AP: The column of fire is mentioned again! Brigit is ordained with apostolic primacy… quite unusual for a woman. Was the compositor of this hagiography a woman?

20

Afterwards the people granted her a place called Ached hÍ in Saltus Avis. Remaining there a little while, she persuaded three pilgrims to remain there and granted them the place. She performed three miracles in that place, namely: The spring flowed in dry land, the meat turned into bread, the hand of one of the three men was cured.

AP: Ached hÍ in Saltus Avis = (?) Island on the plain of the leaping birds: a composite Irish/Latin name. It seems to describe a Crannog… Brigit creates a well, converts meat (a pagan sacrificial offering) to bread, and cures the sick.

21

Once at Eastertide: ‘What shall we do?’, said Brigit to her maidens. ‘We have one sack of malt. It were well for us to prepare it that we might not be without ale over Easter. There area moreover seventeen churches in Mag Tailach. Would that I might keep Easter for them in the matter of ale on account of the Lord whose feast it is, that they might have drink although they should not have food. It is unfortunate for us only that we have no vessels.’ That was true. There was one vat in the house and two tubs. ‘They are good; let it be prepared(?).’

p.25

This is what was done: the mashing in one of the tubs, in the other it was put to ferment; and that which was put to ferment in the second tub, the vat used to be filled from it and taken to each church in turn, so that the vat kept on coming back, but though it came back quickly that which was in the tub was ale. Eighteen vatfuls had come from the one sack, and what sufficed for herself over Easter. And there was no lack of feasting in every single church from Easter Sunday to Low Sunday as a result of that preparation by Brigit.

AP: The pagan tales tell of ever-renewing cauldrons and goblets: this is a Brigitine re-visioning of this theme!

22

A woman from Fid Éoin who was a believer gave her a cow on that Easter Day. There were two of them driving the cow, namely the woman and her daughter. They were not able however to drive their cow . . . They had lost their calf as they were coming through the wood. They besought Brigit then. That prayer availed them; their cow leads the way before them to the settlement where Brigit was. ‘This is what we must do’, said Brigit to her maidens, ‘for this is the first offering made to us since occupying this hermitage, let it be taken to the bishop who blessed the veil on our head.’ ‘It is of little benefit to him’, said the maidens, ‘the cow without the calf.’ ‘That is of no account’, said Brigit. ‘The little calf will come to meet its mother so that it will be together they will reach the enclosure.’ It was done thus as she said.

AP: The cow with calf produces milk… This is the first reference to Brigit herself being involved with droving. The passage deals with the springtime fertility of cattle and onset of milking, as well as the primacy of the celebration of Easter to Christians. There is an allegory here that the faithful must bring their children to the fold, as well…

23

On the same Easter Sunday there came to her a certain leper from whom his limbs were falling, to ask for a cow. ‘For God’s sake, Brigit, give me a cow.’ ‘Grant me a respite’, said Brigit. ‘I would not grant you’, said he, ‘even the respite of a single day.’ ‘My son, let us await the hand of God’, said Brigit. ‘I will go off’, said the leper. ‘I will get a cow in another stead although I obtain it not from you.’ ‘. . .’, said Brigit, ‘and if we were to pray to God for the removal of your leprosy, would you like that?’, ‘No’, said he, ‘I obtain more this way than when I shall be clean.’ ‘It is better’, said Brigit, ‘. . . and you shall take a blessing [and] shall be cleansed.’ ‘All right then’, said he, ‘for I am sorely afflicted.’ ‘How will this man be cleansed?’, said Brigit to her maidens. ‘Not hard, O nun. Let your blessing be put on a mug of water, and let the leper be washed with it afterwards.’ It was done thus and he was completely cured. ‘I shall not go’, said the leper, ‘from the cup which has healed me — I shall be your servant and woodman.’ Thus it was done.

AP: The ‘leper’ becomes the servant after receiving healing. Christianity promoted itself as a healing religion, this being the main biblical power of the apostles. The passage gives the goddess-saint power to bless water for healing. ‘Leprosies’ was a biblical term for diseases inflicted by God – typically ‘cutaneous’ (skin) or visible disorders. The ‘blast’ and the ‘stroke’ from a spiritual agency were two names from Atlantic folklore that described such diseases (‘leprosies’ in the biblical/medieval sense, rather than Hansen’s Disease per se) and these were more often ascribed to fairies rather than the Christian god in folklore accounts!

Brigit’s healing escapades increase now she is a young woman, reflecting the biblical ministry of Jesus once he came of age…

24

On the following day, Monday, Mel came to Brigit to preach and say Mass for her between the two Easters. A cow had been brought to her on that day also and it was given to Mel the bishop, the other cow having been taken. Ague assails one of Brigit’s maidens and she was

p.26

given Communion. ‘Is there anything you might desire?’, said Brigit. ‘There is’, said she. ‘If I do not get some fresh milk, I shall die at once.’ Brigit calls a maiden and said: ‘Bring me my own mug, out of which I drink, full of water. Bring it without anyone seeing it.’ It was brought to her then, and she blessed it so that it became warm new milk, and the maiden was immediately completely cured when she tasted of it. So that those are the two miracles simultaneously, i.e. the changing of water to milk and the cure of the maiden.

AP: Transforming water into healing milk is a transformation of the ‘water-into-wine’ biblical passage into an Irish context! Milk and buttermilk was a popular healing drink down to modern times. It has a maternal, nourishing metaphysical association, so is fitting for the female saint to distribute it. Medieval religious depictions of Mary feeding milk from her breasts to the faithful are worth considering as equivalent. It is even faintly possible that such ‘Maryology’ (for example that promoted by the Cistercian monks throughout Europe from the 12thC) might have been derived from Ireland’s syncretic Brigitine faith…

25

On the following day, Tuesday, there was a good man nearby who was related to Brigit. He had been a full year ailing. ‘Take for me today’, said he, ‘the best cow in my byre to Brigit, and let her pray to God for me, to see if I shall be cured.’ The cow was brought, and Brigit said to those who brought it: ‘Take it immediately to Mel.’ They brought it back to their house and exchanged it for another cow unknown to their sick man. That was related to Brigit, who was angry at the deceit practised on her. ‘Between a short time from now and the morning’, said Brigit, ‘wolves shall eat the good cow which was given into my possession and which was not brought to you’, said she to Mel, ‘and they shall eat seven oxen in addition to it.’ That was related then to the sick man. ‘Go’, said he, ‘take to her seven oxen of choice of the byre.’ It was done thus. ‘Thanks be to God’, said Brigit. ‘Let them be taken to Mel to his church. He has been preaching and saying Mass for us these seven days between the two Easters; a cow each day to him for his labour, it is not greater than what he has given; and take a blessing with all eight, a blessing on him from whom they were brought’, said Brigit. When she said that he was healed immediately.

AP: Easter again linked to healing (of sins, by Jesus’ supposed sacrifice). The giving of tithes – dues to the holy men – seems to be a subtext implied here. Cows and oxen were the wealth of the Irish lords.

26

During the time between the two Easters Brigit suffered greatly from a headache. ‘That does not matter’, said Mel. ‘When we go to visit our first settlement in Tethbae, Brigit and her maidens will go with us. There is a wonderful physician in Mide, namely Aed mac Bricc. He will heal you.’ It was then she healed two paralytic virgins of the Fothairt.

AP: Aed Mac Bricc was pa atron saint of the Uí Néill. Mide = Meath, which came under the dominance of the Clann Cholmáin (a branch of the Uí Néill) in the 5thC. Kildare was part of their territories…

27

Then two blind Britons with a young leper of the sept of Eocchaid came and pray with importunity to be healed. Brigit said to them: ‘Wait a while.’ But they said, ‘You have healed the infirm of your own people and you neglect the healing of foreigners. But at least heal our boy who is of your people.’ And by this the blind are made to see and the leper is cleansed.

AP: Christianity preached ‘illumination’ and cleansing of the harm caused by the beam of evil once believed to have been emitted from the jealous or proud eye. This passage implies that the Christian mission must be spread back East.

28

Low Sunday approached. ‘I do not think it fortunate now’, said

p.27

Brigit to her maidens, ‘not to have ale on Low Sunday for the bishop who will preach and say Mass.’ As soon as she said that, two maidens went to the water to bring in water and they had a large churn for the purpose, and Brigit was not aware of this. When they came back again, Brigit saw them there. ‘Thanks be to God’, said Brigit. ‘God has given us beer for our bishop.’ The nuns became frightened then. ‘May God help us. O maiden.’ ‘Whatever foolish thing I said, I have not said anything evil, O nuns.’ ‘The water which was brought inside, because you have blessed it, God did what you desired and immediately it was changed into ale with the smell of wine from it, and better ale was never set to brew in the [whole] world.’ The one churn was sufficient [for them] with their guests and the bishop.

AP: Yet again, an emphasis upon the creation of health-giving drinks from water.

29

On the Monday after Low Sunday Brigit went in her chariot and her maidens along with her and the two bishops and Mel and Melchú into the plain of Mide to a physician, and that they might go afterwards into the plain of Tethbae to visit a foundation which Mel and Melchú had there. On Tuesday at nightfall they turn aside to the house of a certain Leinsterman of the Uí Brolaig. He received them and out of respect and kindness he entertained the holy Brigit and the bishops. That good man and his wife complained. The wife said: ‘All the children I have given birth to have died, except two daughters and they are dumb since the day of their birth.’ She goes to Ath Firgoirt. The holy Brigit falls in the middle of the ford, the horses being frightened for some unknown reason, and the saint’s head was dashed against a stone and was injured on top, and it richly stained the waters with the blood which was shed. The holy Brigit said to one of the two dumb girls: ‘Pour the water mixed with blood about your neck in the name of God.’ And she did so and said: ‘You have healed me. I give thanks to God’. ‘Call you sister’, said Brigit to the girl who had been healed. ‘Come here, sister’, said she. ‘I shall come indeed’, said her companion, ‘and though I go I have already been healed. I bowed down in the track of the chariot and I was cured.’ ‘Go home’, said Brigit to the girl, ‘and ye shall again bring forth as many male children as have died on you.’ They were delighted at that. And that memorable stone often heals many. Any head with a disease of the head which is placed on it returns from it cured. It was then they met the learned leech, Aed mac Bricc. ‘ . . .’, said the bishop, ‘the head of the holy maiden.’ He touched it and with these words addresses the virgin: ‘The vein of your head, O virgin, has been touched by a physician who is much better than I am.’

AP: This passage recalls a pagan one from the Metrical Dindsenchas when Boand dashes her head. It was also used as a motif in the hagiographical Life of St Declan – he dashes his head against a rock which thereafter was supposed to have healing properties by pilgrims down to the modern day. This is a theme with other precedents in legends and hagiography from Ireland in the post-pagan period… There is also a connection between stones, river fords and heads – possibly a vague reference to idol worship that had been replaced.

30

They go to Tethbae, to the first settlements of the bishops, namely Ardagh. The king of Tethbae was feasting nearby. A churl in the king’s house had done a terrible thing. He let fall a valuable goblet belonging to the king, so that it smashed to pieces against the table in front of the

p.28

king. The vessel was a wonderful one, it was one of the rare treasures of the king. He seized the wretch then, and there was nothing for him but death. One of the two bishops comes to beseech the king. ‘Neither shall I give him to anybody’, said the king, ‘nor shall I give him in exchange for any compensation, but he shall be put to death.’ ‘Let me have from you’, said the bishop, ‘the broken vessel.’ ‘You shall have that’, said the king. The bishop then brought it in his arms to Brigit, relating everything to her. ‘Pray to the Lord for us that the vessel may be made whole.’ She did so and restored it and gave it to the bishop. The bishop comes on the following day with his goblet to the king and [says]: ‘If your goblet should come back to you make whole’, said the bishop, ‘would the captive be released?.’ ‘Not only that, but whatever gifts he should desire, I would give him.’ The bishop shows him the vessel and speaks these words to the king: ‘It is not I who performed this miracle, but holy Brigit’.

AP: The goblet/cauldron/vessel motif returns…

31

When Brigit’s fame had resounded throughout Tethbae, there was a certain pious virgin in Tethbae from whom a message was sent in order that Brigit might go and speak to her, namely Bríg daughter of Coimloch. Brigit went and Bríg herself arose to wash her feet. There was a pious woman ailing at that time. While they were washing Brigit’s feet, that sick person who was in the house sent a maiden to bring her out of the tub some of the water which was put over Brigit’s feet. It was brought to her then and she put it about her face and she was completely cured at once; and after being ailing for a year, she was the only servant that night. When their dishes were put in front of them, Brigit began to watch her dishes intently. ‘May it be fitting for us’, said Bríg, ‘O holy maiden, what do you perceive on your dish?’, ‘I see Satan sitting on the dish in front of me’, said Brigit. ‘If it is possible’, said Bríg, ‘I should like to see him.’ ‘It is possible indeed’, said Brigit, ‘provided that the sign of the cross goes over your eyes first; for anyone who sees the devil and does not bless himself first or . . ., will go mad.’ Bríg blesses herself then and sees that fellow. His appearance seemed ugly to her. ‘Ask, O Brigit’, said Bríg, ‘why has he come.’ ‘Grant an answer to men’, said Brigit. ‘No, O Brigit’, said Satan, ‘you are not entitles to it, for it is not to harm you that I have come.’ ‘Answer me then’, said Bríg, ‘what in particular has brought on to this dish?.’ The demon replied: ‘I dwell here always with a certain virgin, with whom excessive sloth has given me a place.’ And Bríg said, ‘Let her be called.’ When she who was called came: ‘Sain her eyes’, said Bríg, ‘so that she may see him whom she has nourished in her own bosom.’ Her eyes having been sained, she beholds the awful monster. Brigit says to the maiden, now terrified with fear and trembling: ‘Behold you see him whom you have cherished for many years and seasons’. ‘O holy maiden,’ said Bríg, ‘that

p.29

he may never enter this house again.’ ‘He shall not enter this house’, said Brigit, ‘till the day of doom.’ They partake of their food and return thanks to God.

AP: This passage is interesting on a number of levels: Firstly, it deals with the practice of foot-washing as an honorary – something of ancient biblical provenance. It also touches upon an Atlantic belief that dust trodden by people might hold a connection to forms of sin or the Evil Eye and loss of substance: In the Isle of Man, such spiritual or magical assaults were once dealt with universally by procuring such dust and disposing of it in various fashions! Brigit sees Satan in the bowl of water, suggesting both an aspect of this principle at the same time as a divinatory practice of staring into the mirror-reflection of water (ie – seeing the inverted otherworld!). Needless to say, the evil is banished by thesaint’s growing power…

32

Once she was hurrying on the bank of the Inny. There were many apples and sweet sloes in that church. A certain nun gave her a small gift in a basket of bark. When she brought [it] into the house, lepers came at once into the middle of the house to beg of her. ‘Take’, said she, ‘yonder apples’, Then she who had presented the apples [said]: ‘I did not give the gift to lepers.’ Brigit was displeased and said: ‘You act wrongly in prohibiting gifts to the servants of God; therefore your trees shall never bear any fruit.’ And the donor, on going out, sees that all at once her garden bore no fruit, while shortly before it had abundant fruits. And it remains barren for ever, except for foliage.

AP: The saint bestows barrenness as well as fecundity: woe to those who don’t donate to the church! Of interest, the Gaelic words for a church and for a stand of trees are very similar… Here it is implied that a church itself was a source of fruit. This could be an allegorical swipe at a particular institution. Hagiography was a very political art form – one that was sponsored by the Uí Néill dynasties above all others!

33

Another virgin brought her apples and sweet sloes in large quantities. She gave [them] immediately to some lepers who were begging. ‘She who brought it will be sound’, said Brigit. ‘O nun, bless me and my garden.’ ‘May God indeed bless’, said Brigit, ‘that big tree yonder which I see in your garden; may there be sweet apples on it, and sweet sloes as to one third; and that twofold fruit shall not be lacking from it and its offshoots.’ And thus it was done. As the nun went into her garden she saw the alder tree with its fruit, and sweet sloes on it as to one third.

AP: Again, this seems like an allegorical passage with a political undertone.

34

In a certain place, namely Aicheth Fir Leth, two lepers followed Brigit. Great jealousy [of each other] took hold of them. They began to quarrel, but their hands and feet grew stiff. Seeing this, Brigit said: ‘Do penance’. They did so. Not only did she release them, but she healed them of their leprosy.

AP: Jealousy = Envy. One of the ‘spiritual sins’. The use of ‘lepers’ and ‘servants’ or ‘followers’ seems interchangeable and suggests that all are sinners, whose sin gives them a disease. Brigit is the physician for these followers. Remember, ‘leprosy’ in a medieval or biblical context doesn’t necessarily mean the disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae!

35

It was then that two virgins came to Brigit that she might go with them to consecrate their foundation and house along with them. Induae and Indiu were their names. On the way they met a youth [who had come] to speak to the nuns with whom Brigit was going. ‘I have come to you’, said he, ‘from this ill person, that a chariot might be brought to him, so that he might die in the same enclosure with you.’ ‘We have no chariot’, said the nuns. ‘Let my chariot be brought to him’, said Brigit. That is what was done then. They were waiting till matins, until the sick man came. Lepers come to them afterwards in the morning. ‘O Brigit’, said they, ‘give us your chariot, for the sake of Christ.’ ‘Take [it]’, said Brigit, ‘[but] grant us a respite, O ye clients

p.30

of God, so that we may bring the sick man first of all to our house which is quite near us.’ ‘We will not grant’, said they, ‘even the respite of a single hour, unless our chariot is being taken from us anyway.’ ‘Take [it] anyway’, said Brigit. ‘What shall we do’, said the nuns, ‘with our sick man?.’ ‘Not hard’, said Brigit. ‘Let him come with us on foot.’ That is what was done then; he was completely cured on the spot.

AP: It has been commented on by scholars and archaeologists that descriptions from early Irish literature of heroes or saints riding in chariots has not been backed up with archaeological discoveries of such equipment. However, ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence’. The Old Irish term for a chariot was ‘carpat’ from the Latin term carpentum, used in reference to the lightweight chariots of the British and continental Celts of the Iron Age. These were the provenance of the aristocracy, who were sometimes referred to in Irish texts as cairptech. Here dying Irish nobleman wishes to be conveyed by chariot to Brigit, which she afterwards donates to some more lepers!

36

It was then that she washed the feet of the nuns of Cúl Fobair, and healed four of them while washing them, namely a paralytic one, a blind one, a leper and a possessed one.

AP: All of the diseases afflicting these nuns are typical religious fare that had overtones of fairy disease in later Irish folklore: (in order) – the Fairy Stroke, the Evil Eye, the Fairy Blast and one ‘taken’ by fairies! I assume the ‘paralytic’ nun was neither drunk on the copious amounts of booze that the clergy used to make, not suffering from some form of repressed hysterical disorder…

37

It was then that she healed the dumb paralytic at the house of Mac Odráin. It happened that Brigit and the dumb boy were left alone. Some destitute people having come and desired a drink, the holy Brigit looked for the key of the kitchen and did not find it. Being ignorant of the boy’s affliction, she addresses him thus: ‘Where is the key?’, And by this the dumb paralytic boy speaks and ministers.

AP: Again, as with other diseases mentioned in this text, the boy’s ‘dumbness’ must be considered allegorical, especially as it mentions his ministry after being given the ‘gift’ of speech by Brigit upon receiving the key to the kitchen.

38

Shortly afterwards at the beginning of summer: ‘Verily’, said Mel and Melchú to Brigit, ‘it has been related to us that Patrick is coming from the south of Ireland into Mag mBreg. We will go to speak to him. Will you go?.’ ‘I will’, said Brigit, ‘so that I may see him and speak to him, and that he may bless me.’ As they set out, a certain cleric with a great amount of chattels and a following pursues them on the way, to ask [them] to accompany him into Mag mBreg. ‘It is a matter of urgency for us’, said Mel, ‘that our cleric may not escape us.’ ‘Let me find this out from you’, said Brigit, ‘the place in which we will meet in Mag mBreg, and I will wait for this pitiable gathering.’ Brigit waited afterwards for the migratory band. ‘There are twenty maidens with me [coming] along the road’, said Brigit, ‘give them some of the burdens.’ The wretched ones say: ‘Not so let it be done, for you have conferred a greater boon on us, since in your company the road is safe for us’. ‘Are there not two carts [coming] along the road?’, said Brigit. ‘Why is it not they which carry the loads?.’ For she had not looked to see what was in them. Since Brigit entered religion, she never looked aside but only straight ahead. ‘There is a brother of mine’, said the cleric, ‘in one of the carts, who has been paralysed for fourteen years. There is a sister of mine in the other who is blind.’ ‘That is a pity’, said Brigit. They came that night to a certain stream, called the Manae. They all ate that night save only Brigit. On the morrow she healed the two sick people who were along with her, and the loads were put into the carts; and they returned thanks to God.

p.31

39

It was then she healed the household of a plebean on the edge of the sea. Thus it was done. A certain man was working in a cow-pasture, of whom the saint asked why he was working alone. He said: ‘All my family is ill.’ Hearing this, she blessed some water and immediately healed twelve sick members of the man’s family.

40

They come then to Tailtiu. Patrick was there. They were debating an obscure question there, namely a certain woman came to return a son to a cleric of Patrick’s household. Brón was the cleric’s name. ‘How has this been make out?’, said everyone. ‘Not hard’, said the woman. ‘I had come to Brón to have the veil blessed on my head and to offer my virginity to God. This is what my cleric did, he debauched me, so that I have borne him a son.’ As they were debating, Brigit came towards the assembly. Then Mel said to Patrick: ‘The holy maiden Brigit is approaching the assembly, and she will find out for you by the greatness of her grace and the proximity of her miracles whether this is true or false; for there is nothing in heaven or earth which she might request of Christ, which would be refused her. This then is what should be done in this case’, said Mel. ‘She should be called apart out of the assembly about this question, for she will not perform miracles in the presence of holy Patrick.’ Brigit came then. The host rises up before her. She is summoned apart out of the assembly immediately to address the woman, and the clerics excepting Patrick accompany her. ‘Whose yonder child?’, said Brigit to the woman. ‘Brón’s’, said the woman. ‘That is not true’, said Brigit. Brigit made the sign of the cross over her face, so that her head and tongue swelled up. Patrick comes to them then in that great assembly-place. Brigit addresses the child in the presence of the people of the assembly, though it had not yet begun to speak. ‘Who is your father’, said Brigit. The infant replied: ‘Brón the bishop is not my father but a certain low and ill-shaped man who is sitting in the outermost part of the assembly; my mother is a liar.’ They all return thanks to God, and cry out that the guilty one be burned. But Brigit refuses, saying: ‘Let this woman do penance.’ This was done, and the head and tongue lost their swelling. The people rejoiced, the bishop was liberated, and Brigit was glorified.

AP: Brigit holds her own in front of the foreign assembly and gets a bishop off the hook. She causes the mother of the child to suffer what appears to be an attack of angioedema or anaphylaxis in order to shut her up, and then makes her baby tell that another man is in fact the father (it was supposed that the innocent cannot lie, just as we generally suppose today that infants cannot speak…).

41

At the end of the day everybody went apart out of the assembly for hospitality. There was a good man living on the bank of the river called Seir. He sent his slave to the assembly to call Brigit, saying to his household: ‘The holy maiden who performed the wonderful miracle in the assembly-place today, I want her to consecrate my house tonight.’ He welcomed her. ‘Let water be put on our hands’, said her maidens

p.32

to Brigit, ‘here is our food.’ ‘It is of no use now’, said Brigit. ‘For the Lord has shown me that this is a heathen home, with the one exception only of the slave who summoned us. On that account I shall not eat now.’ The good man finds this out, namely that Brigit was fasting until he should be baptized. ‘I have said indeed’, said he, ‘that Patrick and his household would not baptize me. For your sake, however, I will believe’, [said he] to Brigit. ‘I do not mind provided that you be baptized’, said Brigit. ‘There is not a man in orders with me. Let someone go from us to Patrick, so that a bishop or priest may come to baptize this man.’ Brón came and baptized the man with all his household at sunrise. They eat at midday. They return thanks. They come to holy Patrick. Patrick said: ‘You should not go about without a priest. Your charioteer should always be a priest.’ And that was observed by Brigit’s abbesses up to recent times.

AP: Only priests can baptize – Patrick recommends that from now on Brigit goes about with a priest. This is a tacit acceptance of her as an agent for his mission to convert the houses of the aristocracy of Ireland, in particular the lands of the Southern Uí Néill…

42

After that she healed the old peasant woman who was placed in the shadow of her chariot at Cell Shuird in the south of Brega.

43

She healed the possessed man . . . who had gone round the borders. He was brought to Brigit afterwards. Having seen her, he was cured.

AP: Another soul ‘taken’ by the fairies is ‘found’ in Christ…

44

Brigit went afterwards to Cell Lasre. Lassar welcomed her. There was a single milch ewe there which had been milked, and it was killed for Brigit. As they were [there] at the end of the ay, they saw Patrick coming towards the stead. ‘May God help us, O Brigit’, said Lassar. ‘Give us your advice.’ Brigit replied: ‘How much have you?’, She said,: ‘There is no food except twelve loaves, a little milk which you have blessed and a single lamb which has been prepared for you’. This is what [they do]: They all go into her refectory, both Patrick and Brigit, and they were all satisfied. And Lassar gave her her church, and Brigit is venerated there.

AP: Another example of ‘Bread and Fishes’ ministry, which paints the saint with powers exactly equivalent to those of the biblical Jesus! It does not appear that it was considered in any way heretical to do so – she was portrayed as a ‘Female Christ’, to all intents and purposes!

45

She remained the next day in Cell Lasre. A certain man of Kells by origin (?), whom his wife hated, came to Brigit for help. Brigit blessed some water. He took it with him and, his wife having been sprinkled [therewith], she straightaway loved him passionately.

AP: The making of Love Philtres is condemned as a pagan practice by the Penitential of Finnian (said to derive from Finnian of Clonard in the 6thC). Here we see the saint usurping this ability from common people – the church was keeping ‘magic’ for itself and out of the hands of its flock.

46

A certain pious virgin sent to Brigit, in order that Brigit might go to visit her. Fine was her name. From her Cell Fhine was named. She went and remained there. One day wind and rain, thunder and lightning set in. ‘Which of you, O maidens, will go today with our

p.33

sheep into this terrible storm?’, All the maidens were equally reluctant. Brigit answered: ‘I love very much to pasture sheep.’ ‘I do not want you to go’, said Fine. ‘Let my will be done’, said Brigit. She went then and chanted a verse while going:

- Grant me a clear day for Thou art a dear friend, a kingly youth; for the sake of Thy mother, loving Mary, ward off rain, ward off wind.

- My king will do [it] for me, Rain will not fall till the night, On account of Brigit today, Who is going here to the herding.

She stilled the rain and the wind.

AP: This final passage of the surviving text begins to deal with Brigit’s usurped functions as a guardian of flocks and controller of the weather: roles subsumed from what we know from later folklore constituted the Cailleach archetype or ‘goddess’!

The text appears in general to deal with the tripartite forms of womanhood, girl<>woman<>dotage/seniority, although the last part of her life-story is lost. This threefold division was the same as that of the Atlantic goddess herself, who was a regenerating figurative representation of the seasons and nature. It was the purpose of the legend of ‘Saint Brigit’ to replace that of this ‘Fairy Queen’ in a way that the male ‘Patrick’ could not.

(c) 2013 Atlantean Perspective.