Cornwall’s patron saint, Perran or Piran, was said to have come from or studied in Ireland – a contemporary and possible student of Finnian of Clonard. His name may derive from a Brythonic interpretation of the Gaelic name ‘Ciarán’ and he is therefore identified in some medieval hagiographies with both Ciaran of Saighir and (by later scholars) with Ciaran of Clonmacnoise, possibly on account of the geographical sphere of influence of Ireland’s great ‘Celtic Rite’ Abbey of Clonmacnoise. Both of these Ciaráns were said to have studied under Finnian. He is supposed to have lived and died in the 6th century, and to have created his first establishment at the place which bears his name: Perranzabuloe.

Names: The ‘p’ and ‘k’ sounds are interchangeable in the orthophony of the ancient Celtic or Atlantic world. ‘Per’ and ‘Ker’, for instance. As the national saint of Cornwall (Kerniw or Kernow) it is even faintly possible that the name ‘Peran’ or ‘Keran’ and its variants relate somehow to this land, the name being set to suit the geography. There are a number of placenames relating to Peran/Piran/Keran etc apart from Perranzabuloe: Nearby Perranporth is one, but less obviously Polperro (known as ‘Portpira’ in the 13th century) on Cornwall’s south coast is another worth considering, especially as it does not appear to be linked in any way to Piran historically although sharing a similar name. This might suggest a pagan origin with its Christian cover story based on the north coast. Other ‘Piran’ names include Perranaworthal and Perranuthnoe, at which there were churches dedicated to the saint. Of interest is the manner in which the ‘t’ of ‘Patrick’ (ie – the saint) has been aspirated and dissolved in various regional pronunciations, giving the name variants ‘Perrick’ (Cornwall), Pherick (Isle of Man, which also has a place called Perwick) and these have hints of the name ‘Perran’ or ‘Piran’. A St Padarn (or Patran, 6thC) and a St Petroc (6thC) also claim names of a similar root. All of these are strongly linked to Brittany, Cornwall and Wales during the early medieval period. The similitude of these Christian ‘superhero’ names may actually point towards the pagan figure or idea that they were attempting to overlay…

Legendary Sources:

Hagiographies: Life of St Piran (14thC) – This surviving hagiography of ‘Piran’ is actually a copy of the Life of Ciaran of Saighir with details of his life in Cornwall appended. For this reason, the two are believed by many to be the same. Another work by 17thC Cornish Catholic Nicholas Roscarrock gave accounts of Piran and his fellow local saints, some of whose legends he took from known folklore of the day. These have been published by the Devon and Cornwall Record Society, Ed. Nicholas Orme.

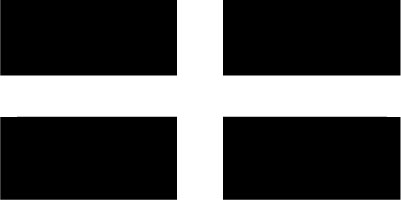

Tin: St Piran (also the patron saint of tin miners) is supposed by a popular anachronistic legend to have discovered tin-smelting, a process which was going on in Cornwall long before christianity. Cornwall’s ‘Perran’s Cross’ flag insignia is said to represent the white metal flowing off Piran’s black (tin ore) hearthstone… Variant names associated with Piran by the tinners included ‘Picrous’ and a character called ‘Chewidden’, said to have discovered white tine along with Perran, Piran or Picrous. Another legend associates Piran with yet another stone:

Arrival from Ireland: Another popular legend says the saint was thrown off a cliff by pagans in Ireland. To ensure his demise they were said to have tied a millstone around his neck, but by divine grace etc this stone floated and Piran, thus saved by God, floated across to Cornwall and landed at the beach near Perranzabuloe/Perranporth where he established his ministry. There are similar curious hagiographic and folklore stories involving Cornish (eg – Petroc who supposedly floated from Ireland to Padstow on his stone altar) and Irish saints (eg – Declan of Ardmore, among others) and floating rocks… In the Isle of Man, there is a story about the Cailleach (Caillagh y Groamagh) that portrays her as an Irish witch thrown into the sea who washes up on a Manx beach at Imbolc/St Brighid’s day. Similarly, the Manx patron saint ‘Maughold’ was said to have been cast adrift from Ireland as a pagan and was Christianised upon landing in Mann… The ‘Irish Nennius’ also tells of a wonder in the Isle of Man – a rock which, although thrown into the sea, returns inland by itself. Such legends seem linked to a probable pagan theme of holy stones and the seashore. Columba’s legendary hagiography also has him making a stone float upon water.